The following text is Chapter IV of Professor Anderson’s forthcoming book entitled The Dirty War on Syria, Global Research Publishers, Montreal, 2016 (forthcoming).

Image. Arms seized by Syrian security forces at al Omari mosque

in Daraa, March 2011. The weapons had been provided by the Saudis.

Photo: SANA

“The protest movement in Syria was overwhelmingly peaceful until September 2011”- Human Rights Watch, March 2012, Washington

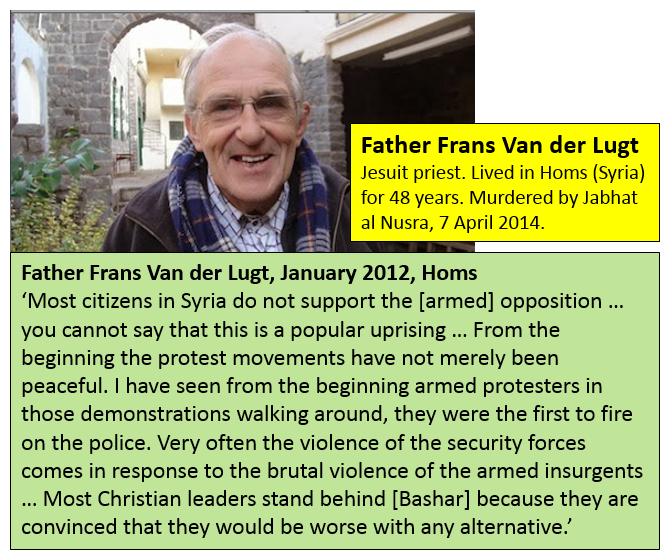

“I have seen from the beginning armed protesters in those

demonstrations … they were the first to fire on the police. Very often

the violence of the security forces comes in response to the brutal

violence of the armed insurgents” – the late Father Frans Van der Lugt, January 2012, Homs Syria

“The claim that armed opposition to the government has begun only

recently is a complete lie. The killings of soldiers, police and

civilians, often in the most brutal circumstances, have been going on

virtually since the beginning”. – Professor Jeremy Salt, October 2011, Ankara Turkey

A

double story began on the Syrian conflict, at the outset of the armed

violence in 2011, in the southern border town of Daraa. The first story

comes from independent witnesses in Syria, such as the late Father Frans

Van der Lugt in Homs. They say that armed men infiltrated the early

political reform demonstrations to shoot at both police and civilians.

This violence came from sectarian Islamists. The second comes from the

Islamist groups (‘rebels’) and their western backers. They claim there

was ‘indiscriminate’ violence from Syrian security forces to repress

political rallies and that the ‘rebels’ grew out of a secular political

reform movement.

Careful study of the independent

evidence, however, shows that the Washington-backed ‘rebel’ story, while

widespread, was part of a strategy to delegitimise the Syrian

Government, with the aim of fomenting ‘regime change’. To understand

this it is necessary to observe that, prior to the armed insurrection of

March 2011 there were shipments of arms from Saudi Arabia to Islamists

at the al Omari mosque. It is also useful to review the earlier Muslim

Brotherhood insurrection at Hama in 1982, because of the parallel myths

that have grown up around both insurrections.

US intelligence (DIA 1982) and the late British author Patrick Seale

(1988) give independent accounts of what happened at Hama. After years

of violent, sectarian attacks by Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood, by mid-1980

President Hafez al Assad had ‘broken the back’ of their sectarian

rebellion, which aimed to impose a Salafi-Islamic state. One final coup

plot was exposed and the Brotherhood ‘felt pressured into initiating’ an

uprising in their stronghold of Hama. Seale describes the start of that

violence in this way:

At 2am on the night of 2-3 February 1982 an army unit

combing the old city fell into an ambush. Roof top snipers killed

perhaps a score of soldiers … [Brotherhood leader] Abu Bakr [Umar

Jawwad] gave the order for a general uprising … hundreds of Islamist

fighters rose … by the morning some seventy leading Ba’athists had been

slaughtered and the triumphant guerrillas declared the city ‘liberated’

(Seale 1988: 332).

However the Army responded with a huge force of about 12,000 and the

battle raged for three weeks. It was a foreign-backed civil war, with

some defections from the army. Seale continues:

As the tide turned slowly in the government’s favour, the

guerrillas fell back into the old quarters … after heavy shelling,

commandos and party irregulars supported by tanks moved in … many

civilians were slaughtered in the prolonged mopping up, whole districts

razed (Seale 1988: 333).

Two months later a US intelligence report said: ‘The total casualties

for the Hama incident probably number about 2,000. This includes an

estimated 300 to 400 members of the Muslim Brotherhood’s elite ‘Secret

Apparatus’ (DIA 1982: 7).

Seale recognises that the Army also suffered heavy losses. At the

same time, ‘large numbers died in the hunt for the gunmen … government

sympathizers estimating a mere 3,000 and critics as many as 20,000 … a

figure of 5,000 to 10,000 could be close to the truth’ He adds:

‘The guerrillas were formidable opponents. They had a fortune in

foreign money … [and] no fewer than 15,000 machine guns’ (Seale 1988:

335). Subsequent Muslim Brotherhood accounts have inflated the

casualties, reaching up to ‘40,000 civilians’, thus attempting to hide

their insurrection and sectarian massacres by claiming that Hafez al

Assad had carried out a ‘civilian massacre’ (e.g. Nassar 2014). The then

Syrian President blamed a large scale foreign conspiracy for the Hama

insurrection. Seale observes that Hafez was ‘not paranoical’, as many US

weapons were captured and foreign backing had come from several US

collaborators: King Hussayn of Jordan, Lebanese Christian militias (the

Israeli-aligned ‘Guardians of the Cedar’) and Saddam Hussein in Iraq

(Seale 1988: 336-337).

The Hama insurrection helps us understand the Daraa violence because,

once again in 2011, we saw armed Islamists using rooftop sniping

against police and government officials, drawing in the armed forces,

only to cry ‘civilian massacre’ when they and their collaborators came

under attack from the Army. Although the US, through its allies, played

an important part in the Hama insurrection, when it was all over US

intelligence dryly observed that: ‘the Syrians are pragmatists who do

not want a Muslim Brotherhood government’ (DIA 1982: vii).

In the case of Daraa, and the attacks that moved to Homs and

surrounding areas in April 2011, the clearly stated aim was once again

to topple the secular or ‘infidel-Alawi’ regime. The front-line US

collaborators were Saudi Arabia and Qatar, then Turkey. The head of the

Syrian Brotherhood, Muhammad Riyad Al-Shaqfa, issued a statement on 28

March which left no doubt that the group’s aim was sectarian. The enemy

was ‘the secular regime’ and Brotherhood members ‘have to make sure that

the revolution will be pure Islamic, and with that no other sect would

have a share of the credit after its success’ (Al-Shaqfa 2011). While

playing down the initial role of the Brotherhood, Sheikho confirms that

it ‘went on to punch above its actual weight on the ground during the

uprising … [due] to Turkish-Qatari support’, and to its general

organisational capacity (Sheikho 2013). By the time there was a ‘Free

Syrian Army Supreme Military Council’ in 2012 (more a weapons conduit

than any sort of army command), it was said to be two-thirds dominated

by the Muslim Brotherhood (Draitser 2012). Other foreign Salafi-Islamist

groups quickly joined this ‘Syrian Revolution’. A US intelligence

report in August 2012, contrary to Washington’s public statements about

‘moderate rebels’, said:

The Salafist, the Muslim Brotherhood and AQI [Al Qaeda in

Iraq, later ISIS] are the major forces driving the insurgency in Syria …

AQI supported the Syrian Opposition from the beginning, both

ideologically and through the media (DIA 2012).

In February 2011 there was popular agitation in Syria, to some extent

influenced by the events in Egypt and Tunisia. There were

anti-government and pro-government demonstrations, and a genuine

political reform movement which for several years had agitated against

corruption and the Ba’ath Party monopoly. A 2005 report referred to ‘an

array of reform movements slowly organizing beneath the surface’ (Ghadry

2005), and indeed the ‘many faces’ of a Syrian opposition, much of it

non-Islamist, had been agitating since about that same time (Sayyid

Rasas 2013). These political opposition groups deserve attention, in

another discussion (see Chapter Five). However only one section of that

opposition, the Muslim Brotherhood and other Salafists, was linked to

the violence that erupted in Daraa. Large anti-government demonstrations

began, to be met with huge pro-government demonstrations. In early

March some teenagers in Daraa were arrested for graffiti that had been

copied from North Africa ‘the people want to overthrow the regime’. It

was reported that they were abused by local police, President Bashar al

Assad intervened, the local governor was sacked and the teenagers were

released (Abouzeid 2011).

Yet the Islamist insurrection was underway, taking cover under the

street demonstrations. On 11 March, several days before the violence

broke out in Daraa, there were reports that Syrian forces had seized ‘a

large shipment of weapons and explosives and night-vision goggles … in a

truck coming from Iraq’. The truck was stopped at the southern Tanaf

crossing, close to Jordan. The Syrian Government news agency SANA said

the weapons were intended ‘for use in actions that affect Syria’s

internal security and spread unrest and chaos.’ Pictures showed ‘dozens

of grenades and pistols as well as rifles and ammunition belts’. The

driver said the weapons had been loaded in Baghdad and he had been paid

$5,000 to deliver them to Syria (Reuters 2011). Despite this

interception, arms did reach Daraa, a border town of about 150,000

people. This is where the ‘western-rebel’ and the independent stories

diverge, and diverge dramatically. The western media consensus was that

protestors burned and trashed government offices, and then ‘provincial

security forces opened fire on marchers, killing several’ (Abouzeid

2011). After that, ‘protestors’ staged demonstrations in front of the

al-Omari mosque, but were in turn attacked.

The Syrian government, on the other hand, said there were unprovoked

attacks on security forces, killing police and civilians, along with the

burning of government offices. There was foreign corroboration of this

account. While its headline blamed security forces for killing

‘protesters’, the British Daily Mail (2011) showed pictures of guns,

AK47 rifles and hand grenades that security forces had recovered after

storming the al-Omari mosque. The paper noted reports that ‘an armed

gang’ had opened fire on an ambulance, killing ‘a doctor, a paramedic

and a policeman’. Media channels in neighbouring countries did report on

the killing of Syrian police, on 17-18 March. On 21 March a Lebanese

news report observed that ‘Seven policemen were killed during clashes

between the security forces and protesters in Syria’ (YaLibnan 2011),

while an Israel National News report said ‘Seven police officers and at

least four demonstrators in Syria have been killed … and the Baath party

headquarters and courthouse were torched’ (Queenan 2011). These police

had been targeted by rooftop snipers.

Even in these circumstances the Government was urging restraint and

attempting to respond to the political reform movement. President

Assad’s adviser, Dr Bouthaina Shaaban, told a news conference that the

President had ordered ‘that live ammunition should not be fired, even if

the police, security forces or officers of the state were being

killed’. Assad proposed to address the political demands, such as the

registration of political parties, removing emergency rules and allowing

greater media freedoms (al-Khalidi 2011). None of that seemed to either

interest or deter the Islamists.

Several reports, including video reports, observed rooftop snipers

firing at crowds and police, during funerals of those already killed. It

was said to be ‘unclear who was firing at whom’ (Al Jazeera 2011a), as

‘an unknown armed group on rooftops shot at protesters and security

forces’ (Maktabi 2011). Yet Al Jazeera (2011b) owned by the Qatari

monarchy, soon strongly suggested that that the snipers were

pro-government. ‘President Bashar al Assad has sent thousands of Syrian

soldiers and their heavy weaponry into Derra for an operation the regime

wants nobody in the word to see’, the Qatari channel said. However the

Al Jazeera suggestion that secret pro-government snipers were killing

‘soldiers and protestors alike’ was illogical and out of sequence. The

armed forces came to Daraa precisely because police had been shot and

killed.

Saudi Arabia, a key US regional ally, had armed and funded extremist

Salafist Sunni sects to move against the secular government. Saudi

official Anwar Al-Eshki later confirmed to BBC television that his

country had sent arms to Daraa and to the al-Omari mosque (Truth Syria

2012). From exile in Saudi Arabia, Salafi Sheikh Adnan Arour called for a

holy war against the liberal Alawi Muslims, who were said to dominate

the Syrian government: ‘by Allah we shall mince [the Alawites] in meat

grinders and feed their flesh to the dogs’ (MEMRITV 2011). The Salafist

aim was a theocratic state or caliphate. The genocidal slogan

‘Christians to Beirut, Alawites to the grave’ became widespread, a fact

reported by the North American media as early as May 2011 (e.g. Blanford

2011). Islamists from the FSA Farouq brigade would soon act on these

threats (Crimi 2012). Canadian analyst Michel Chossudovsky (2011)

observed: ‘The deployment of armed forces including tanks in Daraa [was]

directed against an organised armed insurrection, which has been active

in the border city since March 17-18.”

After those first few days in Daraa the killing of Syrian security

forces continued, but went largely unreported outside Syria.

Nevertheless, independent analyst Sharmine Narwani wrote about the scale

of this killing in early 2012 and again in mid-2014. An ambush and

massacre of soldiers took place near Daraa in late March or early April.

An army convoy was stopped by an oil slick on a valley road between

Daraa al-Mahata and Daraa al-Balad and the trucks were machine gunned.

Estimates of soldier deaths, from government and opposition sources

ranged from 18 to 60. A Daraa resident said these killings were not

reported because: ‘At that time, the government did not want to show

they are weak and the opposition did not want to show they are armed’.

Anti-Syrian Government blogger, Nizar Nayouf, records this massacre as

taking place in the last week of March. Another anti-Government writer,

Rami Abdul Rahman (based in England, and calling himself the ‘Syrian

Observatory of Human Rights’) says:

‘It was on the first of April and about 18 or 19 security forces …

were killed’ (Narwani 2014). Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal Mikdad,

himself a resident of Daraa, confirmed that: ‘this incident was hidden

by the government … as an attempt not to antagonize or not to raise

emotions and to calm things down – not to encourage any attempt to

inflame emotions which may lead to escalation of the situation’ (Narwani

2014).

Yet the significance of denying armed anti-Government killings was

that, in the western media, all deaths were reported as (a) victims of

the Army and (b) civilians. For well over six months, when a body count

was mentioned in the international media, it was usually considered

acceptable to suggest these were all ‘protestors’ killed by the Syrian

Army. For example, a Reuters report on 24 March said Daraa’s main

hospital had received ‘the bodies of at least 37 protestors killed on

Wednesday’ (Khalidi 2011). Notice that all the dead had become

‘protestors’, despite earlier reports on the killing of a number of

police and health workers.

Another nineteen soldiers were gunned down on 25 April, also near

Daraa. Narwani obtained their names and details from Syria’s Defence

Ministry, and corroborated these details from another document from a

non-government source. Throughout April 2011 she calculates that

eighty-eight Syrian soldiers were killed ‘by unknown shooters in

different areas across Syria’ (Narwani 2014). She went on to refute

claims that the soldiers killed were ‘defectors’, shot by the Syrian

army for refusing to fire on civilians. Human Rights Watch, referring to

interviews with 50 unnamed ‘activists’, claimed that soldiers killed at

this time were all ‘defectors’, murdered by the Army (HRW 2011b). Yet

the funerals of loyal officers, shown on the internet at that time, were

distinct. Even Rami Abdul Rahman (the SOHR), keen to blame the Army for

killing civilians, said ‘this game of saying the Army is killing

defectors for leaving – I never accepted this’ (Narwani 2014).

Nevertheless the highly charged reports were confusing.

The violence spread north, with the assistance of Islamist fighters

from Lebanon, reaching Baniyas and areas around Homs. On 10 April nine

soldiers were shot in a bus ambush in Baniyas. In Homs, on April 17,

General Abdo Khodr al-Tallawi was killed with his two sons and a nephew,

and Syrian commander Iyad Kamel Harfoush was gunned down near his home.

Two days later, off-duty Colonel Mohammad Abdo Khadour was killed in

his car (Narwani 2014). North American commentator Joshua Landis (2011a)

reported the death of his wife’s cousin, one of the soldiers in

Baniyas. These were not the only deaths but I mention them because most

western media channels maintain the fiction, to this day, that there was

no Islamist insurrection and the ‘peaceful protestors’ did not pick up

arms until September 2011.

Al Jazeera, the principal Middle East media channel backing the

Muslim Brotherhood, blacked out these attacks, as also the reinforcement

provided by armed foreigners. Former Al Jazeera journalist Ali Hashem

was one of many who resigned from the Qatar-owned station (RT 2012),

complaining of deep bias over their presentation of the violence in

Syria. Hashem had footage of armed men arriving from Lebanon, but this

was censored by his Qatari managers. ‘In a resignation letter I was

telling the executive … it was like nothing was happening in Syria.’ He

thought the ‘Libyan revolution’ was the turning point for Al Jazeera,

marking the end of its standing as a credible media group (Hashem 2012).

Provocateurs were at work. Tunisian jihadist ‘Abu Qusay’ later

admitted he had been a prominent ‘Syrian rebel’ charged with ‘destroying

and desecrating Sunni mosques’, including by scrawling the graffiti

‘There is no God but Bashar’, a blasphemy to devout Muslims. This was

then blamed on the Syrian Army, with the aim of creating Sunni

defections from the Army. ‘Abu Qusay’ had been interviewed by foreign

journalists who did not notice by his accent that he was not Syrian

(Eretz Zen 2014).

US Journalist Nir Rosen, whose reports were generally critical of the

Syrian Government, also attacked the western consensus over the early

violence:

The issue of defectors is a distraction. Armed resistance

began long before defections started … Every day the opposition gives a

death toll, usually without any explanation … Many of those reported

killed are in fact dead opposition fighters but … described in reports

as innocent civilians killed by security forces … and every day members

of the Syrian Army, security agencies … are also killed by anti-regime

fighters (Rosen 2012).

A language and numbers game was being played to delegitimise the

Syrian Government (‘The Regime’) and the Syrian Army (‘Assad

loyalists’), suggesting they were responsible for all the violence. Just

as NATO forces were bombing Libya with the aim of overthrowing the

Libyan Government, US officials began to demand that President Assad

step down. The Brookings Institution (Shaikh 2011) claimed the President

had ‘lost the legitimacy to remain in power in Syria’. US Senators John

McCain, Lindsay Graham and Joe Lieberman said it was time ‘to align

ourselves unequivocally with the Syrian people in their peaceful demand

for a democratic government’ (FOX News 2011). Another ‘regime change’

campaign was out in the open.

In June, US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton dismissed the idea that

‘foreign instigators’ had been at work, saying that ‘the vast majority

of casualties have been unarmed civilians’ (Clinton 2011). In fact, as

Clinton knew very well, her Saudi Arabian allies had armed extremists

from the very beginning. Her casualty assertion was also wrong. The

United Nations (which would later abandon its body count) estimated from

several sources that, by early 2012, there were more than 5,000

casualties, and that deaths in the first year of conflict included 478

police and 2,091 from the military and security forces (OHCHR 2012: 2;

Narwani 2014). That is, more than half the casualties in the first year

were those of the Syrian security forces. That independent calculation

was not reflected in western media reports. Western groups such as Human

Rights Watch, along with US columnists (e.g. Allaf 2012) continued to

claim, even after the early 2012 defeat of the sectarian Farouq-FSA in

Homs, and well into 2012, that Syrian security forces had been

massacring ‘unarmed protestors’, that the Syrian people ‘had no choice’

but to take up arms, and that this ‘protest movement’ had been

‘overwhelmingly peaceful until September 2011’ (HRW 2011a, HRW 2012).

The evidence cited above shows that this story was quite false.

In fact, the political reform movement had been driven off the

streets by Salafi-Islamist gunmen, over the course of March and April.

For years opposition groups had agitated against corruption and the

Ba’ath Party monopoly. However most did not want destruction of what was

a socially inclusive if authoritarian state, and most were against both

the sectarian violence and the involvement of foreign powers. They

backed Syria’s protection of minorities, the relatively high status of

women and the country’s free education and health care, while opposing

the corrupt networks and the feared political police (Wikstrom 2011;

Otrakji 2012).

In June reporter Hala Jaber (2011) observed that about five thousand

people turned up for a demonstration at Ma’arrat al-Numan, a small town

in north-west Syria, between Aleppo and Hama. She says several

‘protestors’ had been shot the week before, while trying to block the

road between Damascus and Aleppo. After some negotiations which reduced

the security forces in the town, ‘men with heavy beards in cars and

pick-ups with no registration plates’ with ‘rifles and rocket-propelled

grenades’ began shooting at the reduced numbers of security forces. A

military helicopter was sent to support the security forces. After this

clash ‘four policemen and 12 of their attackers were dead or dying.

Another 20 policemen were wounded’. Officers who escaped the fight were

hidden by some of the tribal elders who had participated in the original

demonstration. When the next ‘demonstration for democracy’ took place,

the following Friday, ‘only 350 people turned up’, mostly young men and

some bearded militants (Jaber 2011). Five thousand protestors had been

reduced to 350, after the open Salafist attacks.

After months of media manipulations, disguising the Islamist

insurrection, Syrians such as Samer al Akhras, a young man from a Sunni

family, who used to watch Al Jazeera because he preferred it to state

TV, became convinced to back the Syrian government. He saw first-hand

the fabrication of reports on Al Jazeera and wrote, in late June 2011:

I am a Syrian citizen and I am a human. After 4 months of

your fake freedom … You say peaceful demonstration and you shoot our

citizen. From today … I am [now] a Sergeant in the Reserve Army. If I

catch anyone … in any terrorist organization working on the field in

Syria I am gonna shoot you as you are shooting us. This is our land not

yours, the slaves of American fake freedom (al Akhras 2011).

References:

Abouzeid, Rania (2011) ‘Syria’s Revolt, how graffiti stirred an uprising’, Time, 22 March

Daily Mail (2011) ‘Nine protesters killed after security forces open fire by Syrian mosque’, 24 March

Haidar, Ali

(2013) interview with this writer, Damascus 28 December. [Ali Haidar

was President of the Syrian Social National Party (SSNP), a secular

rival to the Ba’ath Party. In 2012 President Bashar al Assad

incorporated him into the Syrian government as Minister for

Reconciliation.]

OHCHR

(2012) ‘Periodic Update’, Independent International Commission of

Inquiry established pursuant to resolution A/HRC/S – 17/1 and extended

through resolution A/HRC/Res/19/22, 24 may, online:

Queenan, Gavriel (2011) ‘Syria: Seven Police Killed, Buildings torched in protests’, Israel National News, Arutz Sheva, March 21

Truth Syria

(2012) ‘Syria – Daraa revolution was armed to the teeth from the very

beginning’, BBC interview with Anwar Al-Eshki, YouTube interview, video

originally uploaded 10 April, latest version 7 November, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FoGmrWWJ77w

Seale, Patrick (1988) Asad: the struggle for the Middle East, University of California Press, Berkeley CA

Dr Tim Anderson is a Senior Lecturer in

Political Economy at the University of Sydney. He researches and writes

on development, rights and self-determination in Latin America, the

Asia-Pacific and the Middle East. He has published many dozens of

chapters and articles in a range of academic books and journals. His

last book was Land and Livelihoods in Papua New Guinea (2015).

|

No comments:

Post a Comment