Even though the U.S. was bankrolling the venture, local leaders were

meant to oversee the vetting of recruits. Yet many, including Shujayi,

were handpicked by U.S. advisors, according to Sardar Wali, then a

district police chief in eastern Uruzgan. Wali was present during the

meeting when U.S. captains pushed for Shujayi to join the local ALP,

despite villager protest that he was neither law-abiding nor from the

area. Rumors about Shujayi abounded: He had ordered 14 men to climb into

a well and then stoned them to death; his troops had burned a young

girl alive and beaten a child to death in front of his mother.

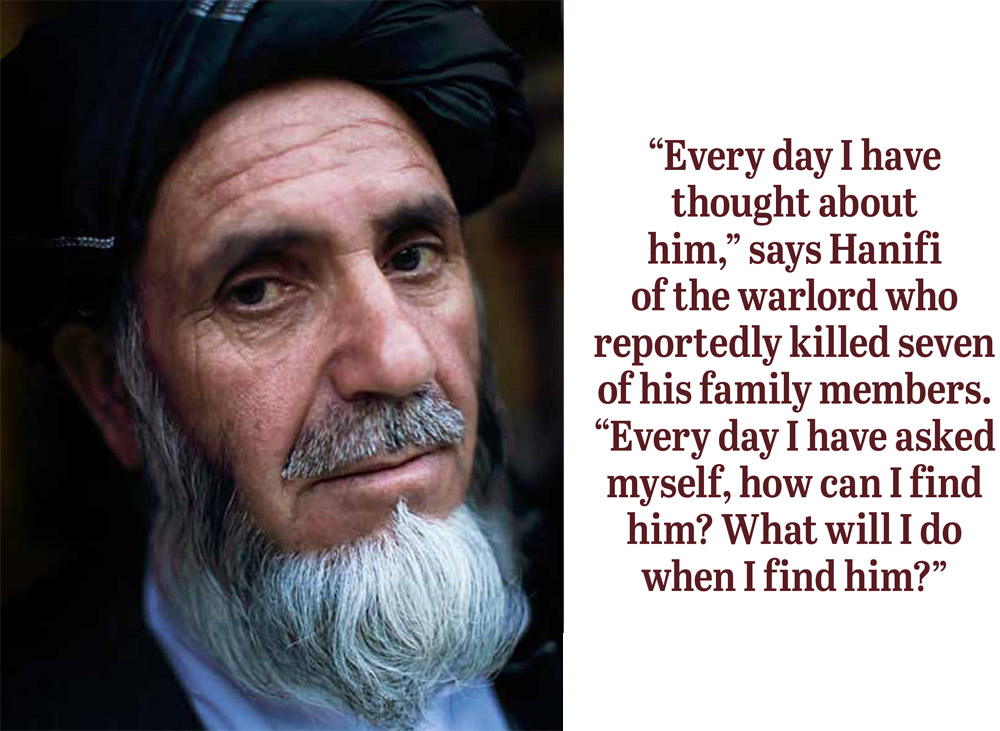

Hanifi

recalled telling the Americans that hiring Shujayi was a terrible plan:

“If you hire only Hazaras, this will create problems. They will kill us

and they will say, ‘Oh, they were Taliban.’ ”

Shujayi was

nonetheless selected. He and the others chosen were fitted with official

uniforms, given weeks-long training by U.S. forces, and sent out into

the communities bearing America’s stamp of approval.

Despite its

more formal structure, in many provinces the ALP proved to be as violent

and unaccountable as its predecessors. In 2011, one year after the

ALP’s creation, Human Rights Watch documented a series of alleged

abuses—extrajudicial killings, torture and sexual assault—that raised

“serious concerns about ALP vetting, recruitment and oversight” and

“questions about the relationship of U.S. forces with abusive members of

the ALP.”

Shujayi was a poster child for the ALP’s excesses—and

its invulnerability. Soon after he was made commander, his officers

reportedly killed two young Pashtun students traveling on a motorcycle,

according to Wali, the former district police chief.

Wali says that when he unofficially inquired about the travellers, Shujayi laughed and said, “The Americans have my back.”

Villagers from eastern Uruzgan issue formal

complaints about Shujayi at their provincial governor’s palace in Tirin

Kot in May 2015. Photo by May Jeong.

4. Flight

In the years following the Khataba massacre, Shujayi became so

notorious that Afghan authorities could no longer ignore the mounting

allegations against him. In a complicated web of alliances that cut

across ethnic, religious and tribal lines, local leaders, politicians,

federal prosecutors and even the head of the ALP tried to bring Shujayi

to justice. All were thwarted, sometimes under inexplicable

circumstances. Shujayi appeared to enjoy protection from powerful men.

In

the summer of 2010, three provincial officials—Uruzgan’s governor,

police chief and finance officer—set out to apprehend Shujayi and charge

him with murder, kidnapping, torture and other crimes. According to

finance officer Abdul Jalil Achekzai, the three found Shujayi at the

U.S. military’s Firebase Anaconda, kitted in the same uniform as the

Americans. Over lunch, the delegation sat negotiating the terms of the

capture with their American hosts. Eventually a captain agreed to let

Shujayi go into their custody, but said the Americans had some

last-minute business to go over in private, and asked the delegation to

wait in the helicopter. After some time, the rotors began to turn, and

the American captain came running out with an interpreter to tell the

delegation that Shujayi had escaped. The disbelieving delegation was

advised to return home before the sky turned dark.

Charles

Cleveland, then-spokesperson for the American mission in Afghanistan,

told me the U.S. military was not aware of the encounter. “While it is

possible that he worked with a U.S. team during 2010, we just don’t have

a record of it,” Cleveland wrote in a February 2016 email.

A

military prosecutor for Uruzgan recalls being part of a similar

delegation in 2012. He says the Americans refused to hand Shujayi over,

repeating that he was a brave soldier who fought the Taliban.

Things

seemed to change in October 2012, when the Afghan interior ministry

issued an order for Shujayi’s immediate capture. Three months later,

interior minister Gholam Mujtaba Patang testified before Parliament that

Shujayi would be detained “within the week.” But Shujayi was never

formally indicted or arrested. According to multiple government sources,

he had allies among influential warlords and officials, who obstructed

efforts to bring him to justice. The Afghanistan Analysts Network

reported that Shujayi spent 2013 traveling frequently to eastern Uruzgan

to oversee security posts there, as if they were still under his

command.

A third near miss occurred in Kabul in 2014. ALP chief

Ali Shah Ahmadzai received a tip that Shujayi was at the interior

ministry and met him with an arrest warrant. Shujayi was taken into

custody. Satisfied, Ahmadzai went home. The next morning, Ahmadzai told

me, he received a phone call from defense minister Bismillah Khan

Mohammadi, who angrily demanded that all charges against Shujayi be

dropped. “He threatened to fire me,” Ahmadzai recalled. Shujayi was

released.

Eight years after the Khataba massacre, he remains a wanted man.

Soon

after, Shujayi dropped out of the public eye. According to U.S.

military spokesperson Cleveland, the commander took “some weapons and

vehicles” and was gone. By that time, eastern Uruzgan locals allege,

Shujayi had killed as many as 60 civilians—all Pashtun villagers. In a

country where few know their date of birth, and where the central

government’s reach does not extend into remote villages, the only

official evidence the villagers had was a list of the dead they had

kept. Among the more than 50 family members, local elders and others I

interviewed for this story, nearly everyone believed Shujayi was to

blame for the deaths.

A villager shares photos of a family member who

was allegedly killed by Shujayi with Afghan senators on a fact-finding

mission in May 2015. Photo by May Jeong.

5. Contact

Shujayi was not just a pariah, a commander gone rogue. Many

commanders before him had committed equally egregious crimes, according

to villagers from eastern Uruzgan, who told me that Shujayi’s

predecessors were also Hazara, and like him, were handpicked by the

Americans. Unlike Shujayi, however, most managed to leverage their

proximity to foreign influence to resettle abroad.

“It needs to

be mentioned that he is not uniquely horrible,” says Uruzgan expert van

Bijlert. “He became strong because of his links to the Americans. He was

artificially propped up because the Americans needed him.” It just so

happened that Shujayi’s reign of terror came as the U.S. special forces

were leaving Uruzgan. His services were no longer needed, and he was

left to fend for himself.

In 2015, a contact connected me with

Sayed Ali, a Hazara fighter and close associate of Shujayi’s. Ali

reflected bitterly upon Shujayi’s treatment by the United States: “The

Americans, they use you like a tissue paper and they throw you away.”

In November 2015, Ali gave me Shujayi’s phone number. After multiple calls, the commander picked up.

“I

am innocent,” Shujayi told me. “I have not committed any crime. I am

being framed because of my ethnicity. I was only doing my job.”

By

then, he had been on the lam for nearly two years. On occasion,

sightings of him were rumored in Kabul. He was said to live freely in

the Hazara area of his native Ghazni province, but no one knew for

certain. When I spoke to Shujayi, he was vague about his whereabouts.

Over a crackling phone line, he did tell me about the vigilante force he

ran, protecting some 5,000 Hazara families living in the borderlands

between Uruzgan and Ghazni province. The group was called niro-e

Shujayi, or the Shujayi brigade.

Shujayi did not express

resentment at those who had pushed him into the life of a fugitive, but

he did want me to note that everyone who had accused him was a Pashtun

(whom Ali derisively calls “Taliban necktie-da,” Taliban with neckties).

Everything they said was slander, he told me. For one, he was

responsible for no more than 30 deaths, all “in battle.” Shujayi said

his level of aggression had been necessary to protect his community.

Which

version of events you believe depends largely on your tribe. Images

hailing Shujayi as a hero of the Hazara people make regular rounds on

Facebook. One advisor to a prominent Hazara ethnic leader, who asked not

to be named because he lives in a majority-Pashtun area and fears

retribution, wanted me to explain why the U.S. military had tacitly

endorsed the behaviors of the Pashtun police chief of Kandahar province,

Abdul Raziq, who was accused of violent abuses, but the international

community gave Shujayi, a Hazara commander, a difficult time over “some

minor misconduct.” (Raziq, while remaining on the Afghan government

payroll, has been implicated in various human rights violations,

including torture and extrajudicial killings.)

“Shujayi is a hero

of the Hazaras,” says Hossain Bahman, a Hazara filmmaker who worked on a

documentary about the commander that aired on a Hazara-owned network.

“He was only defending his family, his own people.”

One thing

that both the Pashtuns and the Hazaras agreed on was how the United

States created the conditions for Shujayi’s rise to power, his

blood-fueled tenure, eventual escape and continued freedom.

Shepard Ambellas

Shepard Ambellas By

By

By

By