FUKUSHIMA

MADE IN JAPAN

When I visited Chernobyl for the first

time 7 years ago, I didn’t think that a similar disaster could take

place anywhere ever again, and certainly not in Japan. After all,

nuclear power is safe and the technology is less and less prone to

failure, and therefore a similar disaster cannot happen in the future.

Scientists said this, firms that build nuclear power stations said this,

and the government said this.

But it did happen.

When I was planning my trip to Fukushima

I didn’t know what to expect. There the language, culture, traditions

and customs are different, and what would I find there four years after

the accident? Would it be something similar to Chernobyl?

THE DISASTER

This photographic documentary is not

intended to tell the story of the events surrounding the disaster yet

again. Like the incident that occurred on 26 April 1986, most readers

know the story well. It is worth mentioning one very important aspect,

however, which is an essential issue as we consider the story further.

It is not earthquakes or tsunami that are to blame for the disaster at

the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station, but humans. The report

produced by the Japanese parliamentary committee investigating the

disaster leaves no doubt about this. The disaster could have been

forseen and prevented. As in the Chernobyl case, it was a human, not

technology, that was mainly responsible for the disaster.

As will be seen shortly, the two disasters have much more in common.

RADIATION OR EVACUATION

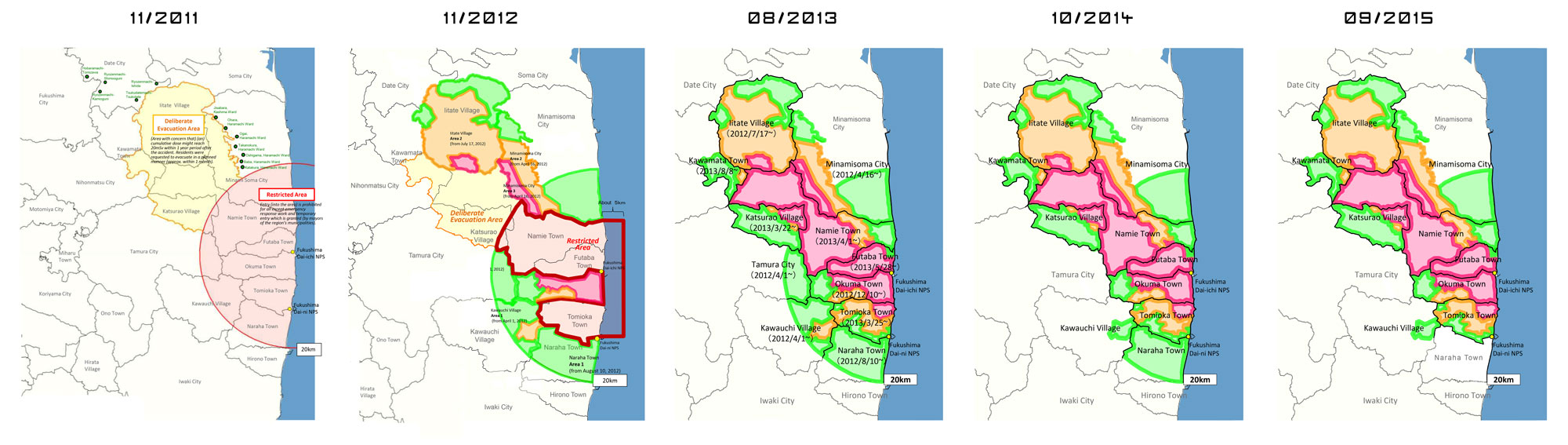

Immediately after the disaster at the

Fukushima power station an area of 3 km, and later 20 km, was designated

from which approximately 160 000 residents were forcibly evacuated.

Chaos, and an inefficient system of monitoring radiation levels,

resulted in many families being divided up or evacuated to places where

the contamination was even greater. In the months and years that

followed, as readings became more precise, the boundaries of the zone

evolved. The zone was divided up according to the level of contamination

and the likelihood that residents would return.

Four years after the accident more than

120 000 people are still not able to return to their homes, and many of

them are still living in temporary accommodation specially built for

them. As with Chernobyl, some residents defied the order to evacuate and

returned to their homes shortly after the disaster. Some never left.

It is not permitted to go to towns and

cities located in the zone with the highest levels of contamination,

marked in red, except with a special permit. Due to the high level of

radiation (> 50 mSv/y), no repair or decontamination work is carried

out there. According to the authorities’ forecasts the residents of

those towns will not be able to return for a long time, if at all.

The orange zone is less contaminated but

also uninhabitable, but because the level of radiation is less (20-50

mSv/y) clearing up and decontamination work is being done here.

Residents are allowed to visit their homes but are still not allowed to

live in them.

The zone with the lowest level of

radiation (< 20 mSv/y) is the green zone, and decontamination work

has been completed here. Now the clean-up is in its final stages, and

soon the evacuation order is to be lifted.

DECONTAMINATION

When entering the zone, the first thing

that one notices is the huge scale of decontamination work. Twenty

thousand workers are painstakingly cleaning every piece of soil. They

are removing the top, most contaminated layer of soil and putting it

into sacks, to be taken to one of several thousand dump sites. The sacks

are everywhere. They are becoming a permanent part of the Fukushima

landscape.

Dump

sites with sacks of contaminated soil are usually located on arable

land. To save space they are stacked in layers, one on top of the other.

The contamination work does not stop at

removal of contaminated soil. Towns and villages are being cleaned as

well, methodically, street by street and house by house. The walls and

roofs of all the buildings are sprayed and scrubbed. The scale of the

undertaking and the speed of work have to be admired. One can see that

the workers are keen for the cleaning of the houses to be completed and

the residents to return as soon as possible.

What the workers, and in fact the

government financing their work, want to achieve is not necessarily what

the residents themselves want. The contaminated land is not reused, and

doesn’t even leave the zone. It is only transported out of the town

often not beyond the outskirts. This expensive operation is only the

shifting of the problem from one place to another, just so long as it is

outside of the town to which residents are soon to return.

It is still not clear where the

contaminated waste will end up, especially as the residents protest

against long-term dump sites being located near their homes. They are

not willing to sell or lease their land for this purpose. They do not

believe the government’s assurances that in 30 years from now the sacks

containing the radioactive waste will be gone. They are worried that the

radioactive waste will be there forever.

Many areas cannot be decontaminated at

all because of thick forests or because they are mountainous. Only

houses and areas surrounding the houses, and 10-metre strips along the

roads, are decontaminated. This gives rise to the reasonable fear on the

part not only of residents, but also of scientists, that any major

downpour will wash radioactive isotopes out of the mountainous, forest

areas and the inhabited land will become contaminated again. The same is

true of fire, which, helped by the wind, can easily carry radioactive

isotopes into the nearby towns. These fears are not without foundation,

over the last year this has happened at least twice in Chernobyl.

Given the situation, the attitude of the

residents, who are distrustful of the authorities, are worried about

contamination, and do not want to return to their homes, is no surprise.

A survey carried out on former residents of the red zone shows that

only 10% of those polled want to return to their homes, while as many as

65% of evacuees do not intend to go back. In fact, what do they have to

return to? The lack of work, infrastructure, and medical care is an

effective deterrent to returning even for the most optimistic residents,

and with each year that passes this will be more difficult; the

residents get older, like the deserted houses they are not renovating.

Are the towns to remain deserted forever?

There are also reasons for an

unwillingness to return that residents do not like to talk about, and

this is the compensation and the various types of subsidies and tax

relief that evacuees receive. The compensation for the moral wrongdoing

alone, that every evacuee gets, is 100 000 yen (approximately 850

dollars). Some residents have protested, and are even taking legal

action against the government, which intends to stop compensation one

year after a zone (the green and orange zones) is opened. The residents

are scared that the authorities’ actions are an attempt to coerce them

into returning, especially as the government arbitrarily raised the

permitted level of exposure to radiation per year from 1 to 20 mSv.

NO-GO ZONE

The decision not to come to Fukushima

until four years after the disaster is a deliberate one, as most of the

destruction caused by the earthquake and tsunami has been cleared up.

Above all, I would like to focus on the accident at the nuclear power

station and the effects it had on the environment and the evacuated

residents, and compare it to Chernobyl. For this reason, what I would

like to do the most is see the orange zone and the red zone, the most

contaminated and completely deserted. In the latter, no clearing up or

decontamination work is going on. Here time has stood still, as if the

accident happened yesterday.

A separate permit is required for each

of the towns in the red zone, which is issued only to people who have a

legitimate, official reason to go there. No tourists are allowed. Even

journalists are not welcome. The authorities are wary, they enquire

after the reason, the topic being covered, and attitude towards the

disaster. They are worried that journalists will not be accurate and

objective when presenting the topic, but they are most likely scared of

being criticized for their actions.

I try to arrange entry into the no-go

zone while still in Poland. I get help from colleagues, authors of

books, and journalists who write about Fukushima. They recommend their

friends, they recommend their friends, and they recommend their friends.

It is not until I travel to Fukushima and spend two weeks there that I

am able to make contact with the right people. It turns out that the

knowledge I have and the photographs I have taken in my career from

numerous visits to Chernobyl convince these people to help me.

While I am waiting for the permits to be

issued I visit the towns in the orange zone. It takes me two days to

find the house of Naoto Matsumura, a farmer who returned illegally to

the zone, which at that time was still the red zone, not long after the

accident. He returned to take care of the abandoned animals. He gives

the reasons for returning, saying that he could not bear to see whole

herds of cattle wandering aimlessly in the empty streets when their

owners had fled the radiation. He tells of how they were starving to

death or were being killed and used for recycling by the authorities.

What have they done wrong that makes it right to kill them for no reason

– he asks, trying to explain why he returned illegally.

When Matsumura finds out that I visit

Chernobyl regularly, the person asking the questions quickly becomes the

person being asked them. Matsumura is curious about how the evacuation

was carried out in Chernobyl, how decontamination was carried out, and

the level of radiation. He asks specific questions, enters into a

discussion, compares the radiation levels. It is clear that due to the

Fukushima disaster he learnt the professional terminology and terms

relating to the issue. Unfortunately time flies relentlessly and

Matsumura has to get back to his duties. We arrange to meet again in the

autumn.

It is still illegal for residents to

return permanently to towns located in the orange zone. They are only

allowed to spend time there in the daytime, but even during the day it

is hard to find any residents here. Most do not want to return, and soon

they won’t have anything to come back to. Many of the deserted houses,

especially the wooden ones, are in such a state of disrepair that soon

it will be not be financially viable to renovate them, and if they are

not renovated they will start to fall down. Maybe this is a conscious

choice on the part of the residents, who allow this to happen because

they have already made up their minds never to return to them?

Young residents or families with

children left Fukushima long ago. In pursuit of a better life, a better

future, they went to Tokyo or other large towns. The older residents,

more attached to the place they have lived for several decades, prefer

to live nearby, in specially built temporary housing. Others went to

relatives, but not for long, so as not to be a burden. They return to

their temporary housing, two tiny rooms and a kitchen in the hall.

Youko

Nozawa takes me to the temporary housing she was moved to after weeks

of moving from place to place during the evacuation. Being invited

inside is quite a privilege and a demonstration of trust for the

Japanese, who value their privacy.

A week later I have the permit in my

hand and can finally make my way to Namie, one of three towns in the

no-go zone. Although the town is completely deserted, the traffic lights

still work, and the street lamps come on in the evening. Now and again a

police patrol also drives by, stopping at every red light despite the

area being completely empty. They also stop next to our car and check

our permits carefully.

I am accompanied by three Namie

residents who want to show me the houses they were evacuated from. The

earthquake did not do any serious damage to the houses, and being

situated a long way from the ocean they were also not at threat from the

killer tsunami wave. It was only the radioactive cloud that forced

residents to flee.

In order to see the effects of the

tsunami we go to the coast, where all of the buildings were destroyed.

Although four years have passed, the clean-up is still going on,

although most of the damage has now been cleared up. Behind the

buildings one concrete building stands out, which was capable of

withstanding the destructive force of the tsunami. It is a school, built

using TEPCO money, where the schoolchildren luckily survived by

escaping to the nearby hills.

The

primary school building that survived is situated a mere 300 metres

from the ocean. On the tower, as in all of the classrooms, there are

clocks which stopped at the moment the tsunami came (at the time the

power went off).

Remains of destruction in the aftermath of the tsunami. A photograph from the school’s observation tower.

Abandoned

vehicles. They can’t be removed until the owners give their consent. In

the background the hills to which the schoolchildren escaped.

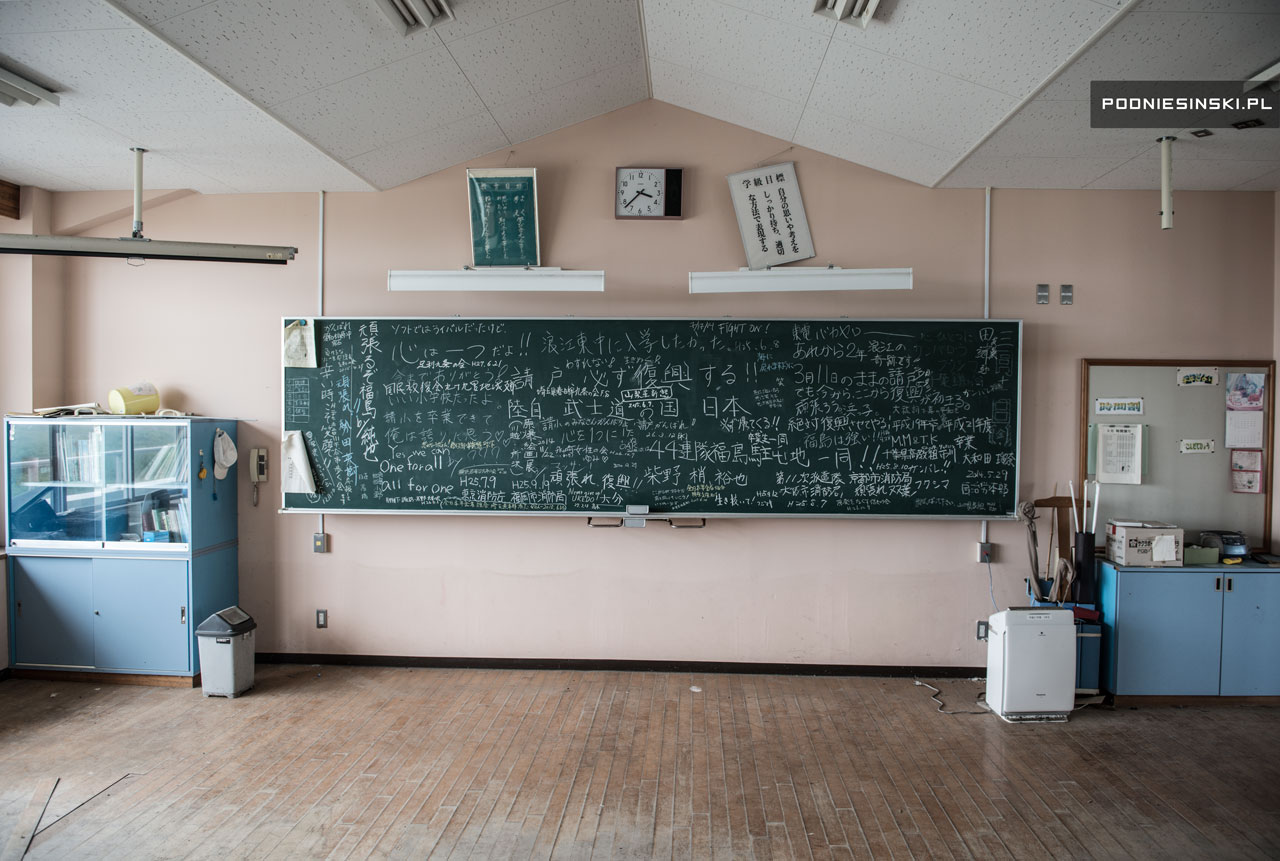

One

of the classrooms on the first floor in the school. There is still a

mark below the blackboard showing the level of the tsunami wave. On the

blackboard in the classroom are words written by former residents,

schoolchildren and workers in an attempt to keep up the morale of all of

the victims, such as / we will be reborn / we can do it, Fukushima! /

stupid TEPCO / we were rivals in softball, but always united in our

hearts! / We will definitely be back! / Despite everything now is

precisely the beginning of our rebirth / I am proud to have graduated

from the Ukedo primary school / Fukushima is strong / Don’t give up,

live on! / Ukedo primary school, you can do it! / if only we could

return to our life by the sea / it’s been two years now and Ukedo

primary school is the same as it was on 11 March 2011, this is the

beginning of a rebirth./

Finally we visit Masami Yoshizawa’s

farm, who, like Matsumura, returned to his ranch shortly after the

disaster to take care of the abandoned animals. Yoshizawa’s story is

more interesting, however. Not long after the accident his cows started

to get mysterious white spots on their skin. Yoshizawa suspects that

this is due to the cows eating contaminated grass. He is trying to

publicise the case, he is in contact with the media, and protests in

front of the Japanese parliament, even taking one of his cows.

Unfortunately, apart from financial support and regular testing of the

cows’ blood, there is no one who is willing to finance more extensive

tests.

There are currently approximately 360 cattle on Masami Yoshizawa’s farm. The cracks in the earth were caused by the earthquake.

Namie at dusk. Despite the area being totally deserted the traffic lights and streetlamps still work.

Another week of waiting and finally I

receive the permit to go to Futaba, another town in the no-go zone. This

town, which borders the ruined power station, is the town with the

highest level of contamination in the zone. There has not been any

clearing up or decontamination due to the radiation being too high. For

this reason we are also issued with protective clothing, masks, and

dosimeters.

The checkpoint in front of the Fukushima II power station. In the background a building of one of the reactors.

The town’s close ties with the nearby

power station are not just a question of the short distance between

them. Next to the main road leading to the town centre I come across a

sign across the street, and in fact it is a slogan promoting nuclear

energy, saying „Nuclear energy is the energy of a bright future” – today

it is an ironic reminder of the destructive effects of using nuclear

power. A few hundred metres further on there is a similar sign.

A message of propaganda above one of the main streets of Futaba – „Nuclear energy is the energy of a bright future”

While I am in Futaba I am accompanied by

a married couple, Mitsuru and Kikuyo Tani (aged 74 and 71), who show me

the house from which they were evacuated. They visit it regularly but

due to the regulations they can do this a maximum of once a month, and

only for a few hours at a time. They take advantage of these

opportunities even though they gave up hope of returning permanently a

long time ago. They check to see if the roof is leaking and whether the

windows have been damaged by the wind or wild animals. If necessary they

make some minor repairs. Their main reason for returning however is

sentimental and the attachment they feel to this place. A yearning for

the place in which they have their origins and spent their entire lives.

The guest room

When visiting Futaba, which borders the

damaged nuclear power station Fukushima I, I can’t help but try to

photograph the main culprit of the nuclear disaster, but unfortunately

all of the roads leading to the power station are closed and are heavily

guarded. With a little ingenuity one can see it, however. But first I

go to see a nearby school.

When leaving the red zone there is a compulsory dosimeter checkpoint.

In the vicinity of the red zone I happen

to notice an abandoned car. It is hard to make it out from a distance,

it is almost completely overgrown with green creepers. When I get up

closer I notice that there are more vehicles, neatly organised in

several rows. I guess that the cars became contaminated and then were

abandoned by the residents. A moment later the beep of the dosimeter

confirms this.

INTERIORS

While I am in the zone I devote a lot of

time and attention to taking photographs of the interiors. Photographs

of this kind give a very good illustration of the human and highly

personal dimension of the tragedy. They also make us aware of what the

residents of Fukushima lost and the very short time they had for the

evacuation. When taking photographs of the interiors of the buildings

the similarities to Chernobyl are even more striking, although in

Chernobyl, after almost 30 years since the disaster and thousands of

tourists visiting it, it is hard to find any untouched objects. One time

a teddy bear is lying completely covered with gasmasks, and a month

later it is next to the window, put there so that a tourist could take a

photograph in better light. These are things that were staged

subsequent to the incident. In Fukushima, the disaster remains seared

into the memories of residents, the evacuation order still in force, and

the total lack of tourists mean that everything is in the same place as

it was four years ago. Toys, electronic devices, musical instruments,

and even money, have been left behind. Only a tragedy on this scale can

produce such depressing scenes.

CONCLUSION

I came to Fukushima as a photographer

and a filmmaker, trying above all to put together a story using

pictures. I was convinced that seeing the effects of the disaster with

my own eyes would mean I could assess the effects of the power station

failure and understand the scale of the tragedy, especially the tragedy

of the evacuated residents, in a better way. This was a way of drawing

my own conclusions without being influenced by any media sensation,

government propaganda, or nuclear lobbyists who are trying to play down

the effects of the disaster, and pass on the information obtained to as

wider a public as possible.

This was only the first trip, I am

coming back to Fukushima in the autumn, and there is nothing to suggest

that I will stop in the near future. This should not be understood as a

farewell to Chernobyl, I will be visiting both places regularly.

Seven years ago I ended my first documentary on Chernobyl with these words:

„An immense experience, not comparable

to anything else. Silence, lack of cries, laughter, tears and only the

wind answers. Prypiat is a huge lesson for our generation.”

Have we learnt anything since then?

MEDIA ABOUT THE PROJECT (with English subtitles)

P.S. If

you are a photographer or a filmmaker and you would like to join me on

my next trip to Fukushima or Chernobyl, please write a few words about

yourself and send them to this address: arek (at) podniesinski (dot)pl.

P.S. 2 If

you would like to be up to date or see photographs which have not been

published, follow me on Facebook or add me as a friend. Some posts can

only be read by people in these groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment