The world economy

Dominant and dangerous

As America’s economic supremacy fades, the primacy of the dollar looks unsustainable

When the buck stops

For decades, America’s economic might legitimised the dollar’s claims

to reign supreme. But, as our special report this week explains, a

faultline has opened between America’s economic clout and its financial

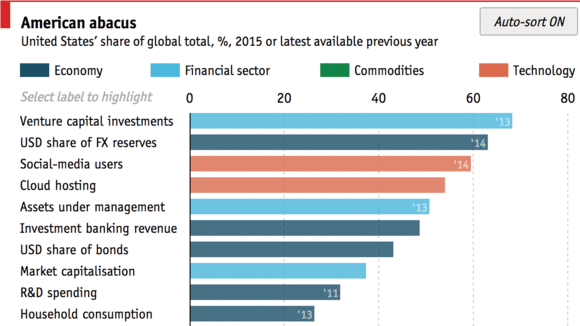

muscle. The United States accounts for 23% of global GDP and 12% of

merchandise trade. Yet about 60% of the world’s output, and a similar

share of the planet’s people, lie within a de facto dollar zone, in

which currencies are pegged to the dollar or move in some sympathy with

it. American firms’ share of the stock of international corporate

investment has fallen from 39% in 1999 to 24% today. But Wall Street

sets the rhythm of markets globally more than it ever did. American fund

managers run 55% of the world’s assets under management, up from 44% a

decade ago.The widening gap between America’s economic and financial power creates problems for other countries, in the dollar zone and beyond. That is because the costs of dollar dominance are starting to outweigh the benefits.

First, economies must endure wild gyrations. In recent months the prospect of even a tiny rate rise in America has sucked capital from emerging markets, battering currencies and share prices. Decisions of the Federal Reserve affect offshore dollar debts and deposits worth about $9 trillion. Because some countries link their currencies to the dollar, their central banks must react to the Fed. Foreigners own 20-50% of local-currency government bonds in places like Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey: they are more likely to abandon emerging markets when American rates rise.

At one time the pain from capital outflows would have been mitigated by the stronger demand—including for imports—that prompted the Fed to raise rates in the first place. However, in the past decade America’s share of global merchandise imports has dropped from 16% to 13%. America is the biggest export market for only 32 countries, down from 44 in 1994; the figure for China has risen from two to 43. A system in which the Fed dispenses and the world convulses is unstable.

A second problem is the lack of a backstop for the offshore dollar system if it faces a crisis. In 2008-09 the Fed reluctantly came to the rescue, acting as a lender of last resort by offering $1 trillion of dollar liquidity to foreign banks and central banks. The sums involved in a future crisis would be far higher. The offshore dollar world is almost twice as large as it was in 2007. By the 2020s it could be as big as America’s banking industry. Since 2008-09, Congress has grown wary of the Fed’s emergency lending. Come the next crisis, the Fed’s plans to issue vast swaplines might meet regulatory or congressional resistance. For how long will countries be ready to tie their financial systems to America’s fractious and dysfunctional politics?

That question is underscored by a third worry: America increasingly uses its financial clout as a political tool. Policymakers and prosecutors use the dollar payment system to assert control not just over wayward bankers and dodgy football officials, but also errant regimes like Russia and Iran. Rival powers bridle at this vulnerability to American foreign policy.

Americans may wonder why this matters to them. They did not force any country to link its currency to the dollar or encourage foreign firms to issue dollar debt. But the dollar’s outsize role does affect Americans. It brings benefits, not least cheaper borrowing. Alongside the “exorbitant privilege” of owning the reserve currency, however, there are costs. If the Fed fails to act as lender of last resort in a dollar liquidity crisis, the ensuing collapse abroad will rebound on America’s economy. And even without a crisis, the dollar’s dominance will present American policymakers with a dilemma. If foreigners continue to accumulate reserves, they will dominate the Treasury market by the 2030s. To satisfy growing foreign demand for safe dollar-denominated assets, America’s government could issue more Treasuries—adding to its debts. Or it could leave foreigners to buy up other securities—but that might lead to asset bubbles, just as in the mortgage boom of the 2000s.

It’s all about the Benjamins

Ideally America would share the burden with other currencies. Yet if

the hegemony of the dollar is unstable, its would-be successors are

unsuitable. The baton of financial superpower has been passed before,

when America overtook Britain in 1920-45. But Britain and America were

allies, which made the transfer orderly. And America came with

ready-made attributes: a dynamic economy and, like Britain, political

cohesiveness and the rule of law (see article).Compare that with today’s contenders for reserve status. The euro is a currency whose very existence cannot be taken for granted. Only when the euro area has agreed on a full banking union and joint bond issuance will those doubts be fully laid to rest. As for the yuan, China’s government has created the monetary equivalent of an eight-lane motorway—a vast network of currency swaps with foreign central banks—but there is no one on it. Until China opens its financial markets, the yuan will be only a bit-player. And until it embraces the rule of law, no investor will see its currency as truly safe.

All this suggests that the global monetary and financial system will not smoothly or quickly wean itself off the greenback. There are things America can do to shoulder more responsibility—for instance, by setting up bigger emergency-swaplines with more central banks. More likely is a splintering of the system, as other countries choose to insulate themselves from Fed decisions by embracing capital controls. The dollar has no peers. But the system that it anchors is cracking.

No comments:

Post a Comment