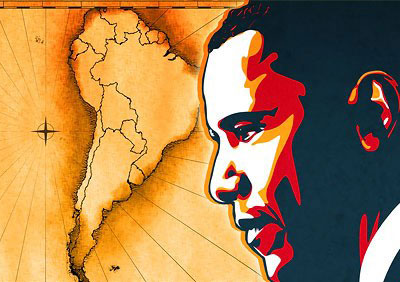

Washington’s “Two Track Policy” to Latin America: Marines to Central America and Diplomats to Cuba

Global Research, May 28, 2015

Url of this article:

http://www.globalresearch.ca/washingtons-two-track-policy-to-latin-america-marines-to-central-america-and-diplomats-to-cuba/5452255

http://www.globalresearch.ca/washingtons-two-track-policy-to-latin-america-marines-to-central-america-and-diplomats-to-cuba/5452255

Everyone,

from political pundits in Washington to the Pope in Rome, including

most journalists in the mass media and in the alternative press, have

focused on the US moves toward ending the economic blockade of Cuba and

gradually opening diplomatic relations. Talk is rife of a ‘major shift’

in US policy toward Latin America with the emphasis on diplomacyand

reconciliation. Even most progressive writers and journals have ceased

writing about US imperialism.

However,

there is mounting evidence that Washington’s negotiations with Cuba are

merely one part of a two-track policy. There is clearly a major US

build-up in Latin America, with increasing reliance on ‘military

platforms’, designed to launch direct military interventions in

strategic countries.

Moreover,

US policymakers are actively involved in promoting ‘client’ opposition

parties, movements and personalities to destabilize independent

governments and are intent on re-imposing US domination.

In

this essay we will start our discussion with the origins and unfolding

of this ‘two track’ policy, its current manifestations, and projections

into the future. We will conclude by evaluating the possibilities of

re-establishing US imperial domination in the region.

Origins of the Two Track Policy

Washington’s

pursuit of a ‘two-track policy’, based on combining ‘reformist

policies’ toward some political formations, while working to overthrow

other regimes and movements by force and military intervention, was

practiced by the early Kennedy Administration following the Cuban

revolution. Kennedy announced a vast new economic program of aid, loans

and investments dubbed the ‘Alliance for Progress’ to promote

development and social reform in Latin American countries willing to

align with the US. At the same time the Kennedy regime escalated US

military aid and joint exercises in the region. Kennedy sponsored a

large contingent of Special Forces ‘Green Berets’ – to engage in

counter-insurgency warfare. The ‘Alliance for Progress’ was

designed to counter the mass appeal of the social-revolutionary changes

underway in Cuba with its own program of ‘social reform’. While Kennedy

promoted watered-down reforms in Latin America, he launched the ‘secret’

CIA (‘Bay of Pigs’) invasion of Cuba in 1961and naval blockade in 1962

(the so-called ‘missile crises’). The two-track policy ended up

sacrificing social reforms and strengthening military repression. By the

mid-1970’s the ‘two-tracks’ became one – force. The US invaded the

Dominican Republic in 1965. It backed a series of military coups

throughout the region, effectively isolating Cuba. As a result, Latin

America’s labor force experienced nearly a quarter century of declining

living standards.

By the

1980’s US client-dictators had lost their usefulness and Washington once

again took up a dual strategy: On one track, the White House

wholeheartedly backed their military-client rulers’ neo-liberal agenda

and sponsored them as junior partners in Washington’s regional hegemony.

On the other track, they promoted a shift to highly controlled

electoral politics, which they described as a ‘democratic transition’,

in order to ‘decompress’ mass social pressures against its military

clients. Washington secured the introduction of elections and promoted

client politicians willing to continue the neo-liberal socio-economic

framework established by the military regimes.

By

the turn of the new century, the cumulative grievances of thirty years

of repressive rule, regressive neo-liberal socio-economic policies and

the denationalization and privatization of the national patrimony had

caused an explosion of mass social discontent. This led to the overthrow

and electoral defeat of Washington’s neo-liberal client regimes.

Throughout

most of Latin America, mass movements were demanding a break with

US-centered ‘integration’ programs. Overt anti-imperialism grew and

intensified. The period saw the emergence of numerous center-left

governments in Venezuela, Argentina, Ecuador, Bolivia, Brazil, Uruguay,

Paraguay, Honduras and Nicaragua. Beyond the regime changes , world

economic forces had altered: growing Asian markets, their demand for

Latin American raw materials and the global rise of commodity prices

helped to stimulate the development of Latin American-centered regional

organizations outside of Washington’s control.

Washington

was still embedded in its 25 year ‘single-track’ policy of backing

civil-military authoritarian and imposing neo-liberal policies and was

unable to respond and present a reform alternative to the

anti-imperialist, center-left challenge to its dominance. Instead,

Washington worked to reverse the new party- power configuration. Its

overseas agencies, the Agency for International Development (AID), the

Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and embassies worked to destabilize the

new governments in Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Paraguay and Honduras.

The US ‘single-track’ of intervention and destabilization failed

throughout the first decade of the new century (with the exception of

Honduras and Paraguay.

In

the end Washington remained politically isolated. Its integration

schemes were rejected. Its market shares in Latin America declined.

Washington not only lost its automatic majority in the Organization of

American States (OAS), but it became a distinct minority.

Washington’s

‘single track’ policy of relying on the ‘stick’ and holding back on the

‘carrot’ was based on several considerations: The Bush and Obama

regimes were deeply influenced by the US’s twenty-five year domination

of the region (1975-2000) and the notion that the uprisings and

political changes in Latin America in the subsequent decade were

ephemeral, vulnerable and easily reversed. Moreover, Washington,

accustomed to over a century of economic domination of markets,

resources and labor, took for granted that its hegemony was unalterable.

The White House failed to recognize the power of China’s growing share

of the Latin American market. The State Department ignored the capacity

of Latin American governments to integrate their markets and exclude the

US.

US State Department

officials never moved beyond the discredited neo-liberal doctrine that

they had successfully promoted in the 1990’s. The White House failed to

adopt a ‘reformist’ turn to counter the appeal of radical

reformers like Hugo Chavez, the Venezuelan President. This was most

evident in the Caribbean and the Andean countries where President Chavez

launched his two ‘alliances for progress’: ‘Petro-Caribe’

(Venezuela’s program of supplying cheap, heavily subsidized, fuel to

poor Central American and Caribbean countries and heating oil to poor

neighborhoods in the US) and ‘ALBA’ (Chavez’ political-economic

union of Andean states, plus Cuba and Nicaragua, designed to promote

regional political solidarity and economic ties.) Both programs were

heavily financed by Caracas. Washington failed to come up with a

successful alternative plan.

Unable

to win diplomatically or in the ‘battle of ideas’, Washington resorted

to the ‘big stick’ and sought to disrupt Venezuela’s regional economic

program rather than compete with Chavez’ generous and beneficial aid

packages. The US’ ‘spoiler tactics’ backfired: In 2009, the Obama regime

backed a military coup in Honduras, ousting the elected liberal

reformist President Zelaya and installed a bloody tyrant, a throwback to

the 1970s when the US backed Chilean coup brought General Pinochet to

power. Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, in an act of pure political

buffoonery, refused to call Zelaya’s violent ouster a coup and moved

swiftly to recognize the dictatorship. No other government backed the US

in its Honduras policy. There was universal condemnation of the coup,

highlighting Washington’s isolation.

Repeatedly,

Washington tried to use its ‘hegemonic card’ but it was roundly

outvoted at regional meetings. At the Summit of the Americas in 2010,

Latin American countries overrode US objections and voted to invite Cuba

to its next meeting, defying a 50-year old US veto. The US was left

alone in its opposition.

The

position of Washington was further weakened by the decade-long

commodity boom (spurred by China’s voracious demand for agro-mineral

products). The ‘mega-cycle’ undermined US Treasury and State

Department’s anticipation of a price collapse. In previous cycles,

commodity ‘busts’ had forced center-left governments to run to the US

controlled International Monetary Fund (IMF) for highly conditioned

balance of payment loans, which the White House used to impose its

neo-liberal policies and political dominance. The ‘mega-cycle’ generated

rising revenues and incomes. This gave the center-left governments

enormous leverage to avoid the ‘debt traps’ and to marginalize the IMF.

This virtually eliminated US-imposed conditionality and allowed Latin

governments to pursue populist-nationalist policies. These policies

decreased poverty and unemployment. Washington played the ‘crisis card’

and lost. Nevertheless Washington continued working with extreme

rightwing opposition groups to destabilize the progressive governments,

in the hope that ‘come the crash’, Washington’s proxies would ‘waltz

right in’ and take over.

The Re-Introduction of the ‘Two Track’ PolicyAfter a decade and a half of hard knocks, repeated failures of its ‘big stick’ policies, rejection of US-centered integration schemes and multiple resounding defeats of its client-politicians at the ballot box, Washington finally began to ‘rethink’ its ‘one track’ policy and tentatively explore a limited ‘two track’ approach.

The

‘two-tracks’, however, encompass polarities clearly marked by the

recent past. While the Obama regime opened negotiations and moved toward

establishing relations with Cuba, it escalated the military threats

toward Venezuela by absurdly labeling Caracas as a ‘national security threat to the US.’

Washington

had woken up to the fact that its bellicose policy toward Cuba had been

universally rejected and had left the US isolated from Latin America.

The Obama regime decided to claim some ‘reformist credentials’ by showcasing its opening to Cuba. The ‘opening to Cuba’

is really part of a wider policy of a more active political

intervention in Latin America. Washington will take full advantage of

the increased vulnerability of the center-left governments as the

commodity mega-cycle comes to an end and prices collapse. Washington

applauds the fiscal austerity program pursued by Dilma Rousseff’s regime

in Brazil. It wholeheartedly backs newly elected Tabaré Vázquez’s

“Broad Front” regime in Uruguay with its free market policies and

structural adjustment. It publicly supports Chilean President Bachelet’s

recent appointment of center-right, Christian Democrats to Cabinet

posts to accommodate big business.

These

changes within Latin America provide an ‘opening’ for Washington to

pursue a ‘dual track’ policy: On the one hand Washington is increasing

political and economic pressure and intensifying its propaganda campaign

against ‘state interventionist’ policies and regimes in the immediate

period. On the other hand, the Pentagon is intensifying and escalating

its presence in Central America and its immediate vicinity. The goal is

ultimately to regain leverage over the military command in the rest of

the South American continent.

The

Miami Herald (5/10/15) reported that the Obama Administration had sent

280 US marines to Central America without any specific mission or

pretext. Coming so soon after the Summit of the Americas in Panama

(April 10 -11, 2015), this action has great symbolic importance. While

the presence of Cuba at the Summit may have been hailed as a diplomatic

victory for reconciliation within the Americas, the dispatch of hundreds

of US marines to Central America suggests another scenario in the

making.

Ironically,

at the Summit meeting, the Secretary General of the Union of South

American Nations (UNASUR), former Colombian president (1994-98) Ernesto

Samper, called for the US to remove all its military bases from Latin

America, including Guantanamo: “A good point in the new agenda of relations in Latin America would be the elimination of the US military bases”.

The point of the US ‘opening’

to Cuba is precisely to signal its greater involvement in Latin

America, one that includes a return to more robust US military

intervention. The strategic intent is to restore neo-liberal client

regimes, by ballots or bullets.

Conclusion

Washington’s current adoption of a two-track policy is a ‘cheap version’ of the John F. Kennedy policy of combining the ‘Alliance for Progress’ with the ‘Green Berets’.

However, Obama offers little in the way of financial support for

modernization and reform to complement his drive to restore neo-liberal

dominance.

After a decade

and a half of political retreat, diplomatic isolation and relative loss

of military leverage, the Obama regime has taken over six years to

recognize the depth of its isolation. When Assistant Secretary for

Western Hemisphere Affairs, Roberta Jacobson, claimed she was ‘surprised and disappointed’ when every Latin American country opposed Obama’s claim that Venezuela represented a ‘national security threat to the United States’,

she exposed just how ignorant and out-of-touch the State Department has

become with regard to Washington’s capacity to influence Latin America

in support of its imperial agenda of intervention.

With

the decline and retreat of the center-left, the Obama regime has been

eager to exploit the two-track strategy. As long as the FARC-President

Santos peace talks in Colombia advance, Washington is likely to

recalibrate its military presence in Colombia to emphasize its

destabilization campaign against Venezuela. The State Department will

increase diplomatic overtures to Bolivia. The National Endowment for

Democracy will intensify its intervention in this year’s Argentine

elections.

Varied and

changing circumstances dictate flexible tactics. Hovering over

Washington’s tactical shifts is an ominous strategic outlook directed

toward increasing military leverage. As the peace negotiations between

the Colombian government and FARC guerrillas advance toward an accord,

the pretext for maintaining seven US military bases and several thousand

US military and Special Forces troops diminishes. However, Colombian

President Santos has given no indication that a ‘peace agreement’

would be conditioned on the withdrawal of US troops or closing of its

bases. In other words, the US Southern Command would retain a vital

military platform and infrastructure capable of launching attacks

against Venezuela, Ecuador, Central America and the Caribbean. With

military bases throughout the region, in Colombia, Cuba (Guantanamo),

Honduras (Soto Cano in Palmerola), Curacao, Aruba and Peru, Washington

can quickly mobilize interventionary forces. Military ties with the

armed forces of Uruguay, Paraguay, and Chile ensure continued joint

exercises and close co-ordination of so-called ‘security’ policies in

the ‘Southern Cone’ of

Latin America. This strategy is specifically designed to prepare for

internal repression against popular movements, whenever and wherever

class struggle intensifies in Latin America. The two-track policy, in

force today, plays out through political-diplomatic and military

strategies.

In the immediate

period throughout most of the region, Washington pursues a policy of

political, diplomatic and economic intervention and pressure. The White

House is counting on the ‘rightwing swing’ of former

center-left governments to facilitate the return to power of unabashedly

neo-liberal client-regimes in future elections. This is especially true

with regard to Brazil and Argentina.

The ‘political-diplomatic track’

is evident in Washington’s moves to re-establish relations with Bolivia

and to strengthen allies elsewhere in order to leverage favorable

policies in Ecuador, Nicaragua and Cuba. Washington proposes to offer

diplomatic and trade agreements in exchange for a ‘toning down’ of

anti-imperialist criticism and weakening the ‘Chavez-era’ programs of

regional integration.

The ‘two-track approach’,

as applied to Venezuela, has a more overt military component than

elsewhere. Washington will continue to subsidize violent paramilitary

border crossings from Colombia. It will continue to encourage domestic

terrorist sabotage of the power grid and food distribution system. The

strategic goal is to erode the electoral base of the Maduro government,

in preparation for the legislative elections in the fall of 2015. When

it comes to Venezuela, Washington is pursuing a ‘four step’ strategy:

(1) Indirect violent intervention to erode the electoral support of the government

(2) Large-scale financing of the electoral campaign of the legislative opposition to secure a majority in Congress

(3) A massive media campaign in favor of a Congressional vote for a referendum impeaching the President

(4) A large-scale financial, political and media campaign to secure a majority vote for impeachment by referendum.

In

the likelihood of a close vote, the Pentagon would prepare a rapid

military intervention with its domestic collaborators seeking a

‘Honduras-style’ overthrow of Maduro.

The

strategic and tactical weakness of the two-track policy is the absence

of any sustained and comprehensive economic aid, trade and investment

program that would attract and hold middle class voters. Washington is

counting more on the negative effects of the crisis to restore its

neo-liberal clients. The problem with this approach is that the pro-US

forces can only promise a return to orthodox austerity programs,

reversing social and public welfare programs , while making large-scale

economic concessions to major foreign investors and bankers. The

implementation of such regressive programs are going to ignite and

intensify class, community-based and ethnic conflicts.

The ‘electoral transition’

strategy of the US is a temporary expedient, in light of the highly

unpopular economic policies, which it would surely implement. The

complete absence of any substantial US socio-economic aid to cushion the

adverse effects on working families means that the US client-electoral

victories will not last long. That is why and where the US strategic

military build-up comes into play: The success of track-one, the pursuit

of political-diplomatic tactics, will inevitably polarize Latin

American society and heighten prospects for class struggle. Washington

hopes that it will have its political-military client-allies ready to

respond with violent repression. Direct intervention and heightened

domestic repression will come into play to secure US dominance.

The ‘two-track strategy’ will, once again, evolve into a ‘one-track strategy’

designed to return Latin America as a satellite region, ripe for

pillage by extractive multi-nationals and financial speculators.

As

we have seen over the past decade and a half, ‘one-track policies’ lead

to social upheavals. And the next time around the results may go far

beyond progressive center-left regimes toward truly social-revolutionary

governments!

Epilogue

US

empire-builders have clearly demonstrated throughout the world their

inability to intervene and produce stable, prosperous and productive

client states (Iraq and Libya are prime examples). There is no reason to

believe, even if the US ‘two-track policy’ leads to temporary

electoral victories, that Washington’s efforts to restore dominance will

succeed in Latin America, least of all because its strategy lacks any

mechanism for economic aid and social reforms that could maintain a

pro-US elite in power. For example, how could the US possibly offset

China’s $50 billion aid package to Brazil except through violence and

repression.

It is important

to analyze how the rise of China, Russia, strong regional markets and

new centers of finance have severely weakened the efforts by client

regimes to realign with the US. Military coups and free markets are no

longer guaranteed formulas for success in Latin America: Their past

failures are too recent to forget.

Finally the ‘financialization’ of the US economy, what even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) describes as the negative impact of ‘too much finance’

(Financial Times 5/13/15, p 4), means that the US cannot allocate

capital resources to develop productive activity in Latin America. The

imperial state can only serve as a violent debt collector for its banks

in the context of large-scale unemployment. Financial and extractive

imperialism is a politico-economic cocktail for detonating social

revolution on a continent-wide basis – far beyond the capacity of the US

marines to prevent or suppress.

No comments:

Post a Comment