Is war between China and the US inevitable? A new book looks to the past for answers

American political

analyst Graham Allison’s thought-provoking book Destined for War ponders

whether the two superpowers can avoid the precedents of history, and

highlights North Korea as a potential flashpoint

More on

this story

this story

In September 2015,

Chinese President Xi Jinping landed in Seattle to begin his first

official visit to the United States. Before meetings with leaders of

major companies such as Microsoft and Boeing, and, later, those in the

White House, Xi gave a speech about relations between the two nations.

Among an impressive array of cultural references – from the movie Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and television series House of Cards

to Ernest Hemingway – it was easy to miss a passage in which Xi

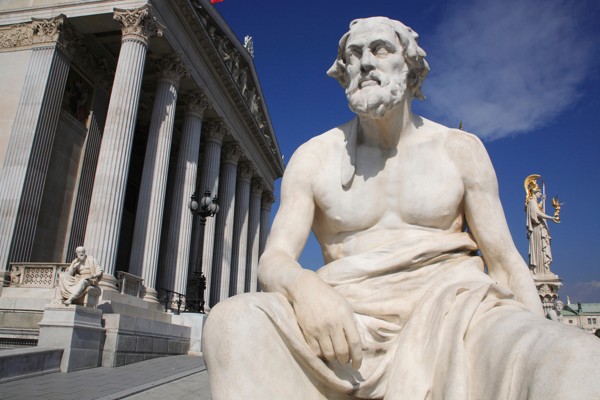

name-checked Thucydides, the Greek historian who pre-dates the author of

The Old Man and the Sea by some 2,500 years.

“We should strictly base

our judgment on facts, lest we become victims to hearsay, paranoid or

self-imposed bias,” Xi said. “There is no such thing as the so-called

Thucydides Trap in the world. But should major countries time and again

make the mistakes of strategic miscalculation, they might create such

traps for themselves.”

Anyone wondering what a “Thucydides Trap” might be should read the new book Destined for War,

by American political scientist Graham Allison, a professor at the John

F Kennedy School of Government, at Harvard University, who not only

coined the phrase but has extrapolated from it an entire theory

concerning the rivalry between China and the US.

“I think Thucydides would

have no problem in saying this looks like a classic Thucydidean

dynamic,” Allison says. “In the same way that Germany and Britain were

idealised Thucydidean analogues of Athens and Sparta, so too with China

and the US.”

What makes a Thucydides

Trap so potentially alarming, Allison argues, is that it tends to

conclude with conflict. Among hostilities studied by Allison are the two

world wars, the first Sino-Japanese war (1894-95) and the

Russo-Japanese war a decade later. Published in May, Destined for War’s

sobering forecast for current Sino-American relations is that “on the

current trajectory, war between the US and China in the decades ahead

is not just possible, but more likely than currently recognised”.

No wonder Xi is paying close attention.

[China]

is an amazing country. I have a huge admiration for what is quite

clearly the phenomenon of our lifetime, the extent of which exhausts the

parade of superlatives. China has gone from nowhere to rivalry [with

the US] or supremacy on every domain

Allison has just returned to his Harvard office after a morning lecture delivered to a class of Chinese entrepreneurs.

“Harvard Business School

runs various executive programmes for 30-somethings from family-owned

businesses in China,” he tells Post Magazine, “which the Communist Party

was undoing, but which are now the fastest-growing part of the economy

in China’s history.”

Allison is fulsome in his

praise for the “50 up and comers” who are “amazed at what’s happening

[in China] but full of enthusiasm”, and he did not neglect to include a

brief tutorial-cum-trailer for his new book. “In the class, we [learned

to pronounce Thucydides] in unison five times so they would be able to

go home and tell people,” he says.

China and the US are destined for war, if literary alarmists have their way

The fact that leaders such

as Xi are paying heed to Allison is not surprising: in the field of

international relations, he is an acknowledged colossus. During a career

spanning half a century, he has counselled US presidents Ronald Reagan

and Bill Clinton, as well as directors of the CIA. He has advised major

oil companies and Wall Street banks, and taken the role of America’s

assistant secretary of defence for policy and plans, with a special

brief for the then Soviet Union.

Essence of Decision by Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow

Essence of Decision by Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow

He

mainly operates, however, in academia. Aside from brief hiatuses at

Britain’s Oxford University and Davidson College, in the US state of

North Carolina, Allison has spent his entire career at Harvard.

His PhD, which was partly supervised by American diplomat Henry Kissinger, was eventually published as Essence of Decision

(1971), the book that established Allison’s international reputation.

An exploration of three models to explain the 1962 Cuban missile crisis,

it helped determine the direction of Harvard’s John F Kennedy School of

Government, where Allison was dean for more than a decade.

Allison formulated the

Thucydides Trap during his tenure as director of Harvard’s Belfer Center

for Science and International Affairs. Its inspiration was a single

sentence in the Greek historian’s account of the Peloponnesian war

(431BC-404BC): “It was the rise of Athens, and the fear that this

instilled in Sparta, that made war inevitable.”

The underlying hypothesis

is that insecurity sparked between an ambitious, rapidly rising nation

and an established power desperate to maintain the status quo vastly

increases the chances of war.

Allison tested his concept

against 16 cases drawn from the past 500 years, beginning in the 15th

century with Spain challenging Portugal. Four of Allison’s 16 Thucydides

Traps ended peacefully thanks to intelligent diplomacy, well-judged

concessions and good fortune. Twelve resulted in disaster.

Insecurities and bluster: the roots of distrust between China and the US

While Destined for War

devotes time to these historic precedents, its focus is on present and

future relations between China and the US, and Allison’s respect for the

former is hard to miss. “[China] is an amazing country,” he enthuses.

“I have a huge admiration for what is quite clearly the phenomenon of

our lifetime, the extent of which exhausts the parade of superlatives.

China has gone from nowhere to rivalry [with the US] or supremacy on

every domain. The world has never seen anything like this before.”

This admiration has its

limits, however. “As someone who admires achievement, I am amazed [by

China],” Allison says. “On the other hand, as an American who knows in

his bones that US means number one, I am terrified.”

A wood engraving depicts Spartans defending Methoni against the Athenians during the Peloponnesian war. Picture: Alamy

A wood engraving depicts Spartans defending Methoni against the Athenians during the Peloponnesian war. Picture: Alamy

Destined for War, among other things, is Allison’s attempt to understand such feelings.

“I was stumbling around,

trying to understand what is clearly the most important bilateral

relationship in the world,” he says. “As I tried to understand, I was

constantly reminded of Thucydides’ insight and I dug in.”

As befits a

Harvard academic of considerable standing, Allison has some impressive

authorities to guide his research – he names Kissinger, British

historian Niall Ferguson and former Australian prime minister Kevin

Rudd, among many others. Allison’s critics have been quick to point out

how white, Western and Harvard-based these advisers are.

In the Trump era, we can’t rule out war between China and the US, whether over trade or security

“I am sure I haven’t

really penetrated the Chinese mindset,” Allison admits. “I am not a

China scholar. I don’t read or speak Mandarin. [China] was never my

topic. But for the past 10 years it has been the subject of very serious

study.”

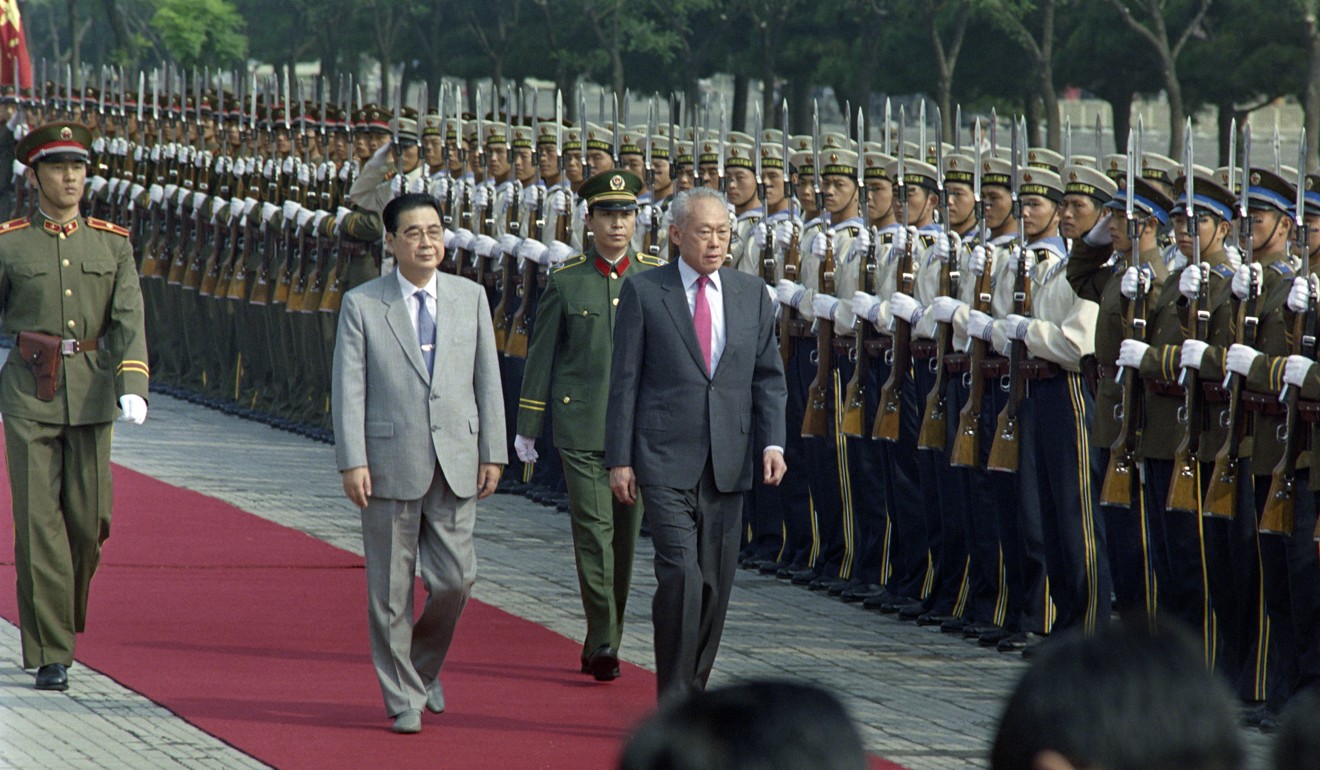

No one did more to shape

Allison’s thinking about China than Singapore’s political architect and

first prime minister, the late Lee Kuan Yew. Allison argues that Lee was

perfectly positioned to translate China for an American audience.

“Lee knew that Singapore

only survived with the forbearance of China,” says Allison. “He studied

carefully how they could survive in the shadow of China.”

A statue of Greek philosopher Thucydides stands in front of the Austrian parliament. Picture: Alamy

A statue of Greek philosopher Thucydides stands in front of the Austrian parliament. Picture: Alamy

According to Allison, this meant seeking counterweights to Chinese power in Asia, whether they be India or the US.

“Lee was very concerned

that the US remains a powerful player in Asia to keep some balance,” he

says. “He feared, I think rightly, that China left to its own devices is

a pretty cruel master.”

Lee and Allison’s long

personal association dated back to 1969. Lee was on “sabbatical when he

was building Singapore and came to Harvard”, says Allison, who was then a

graduate student and Lee’s guide throughout his four-month stay at the

university’s Institute of Politics. “I became interested in the man and

the family, and watched Singapore from a distance.”

China’s cash and American troops are inspiring fine balancing act from US allies in East Asia

A book of Allison’s conversations with Lee, titled Lee Kuan Yew: The Grand Master’s Insights on China, the United States, and the World , was published in 2013. Destined for War

begins with a light-hearted reference to those dialogues. Allison

presented a transcript of his talks with Lee to David Petraeus, then the

new director of the CIA.

“I pretended to have a

report of a deep ‘sleeper’ agent who had studied China for 25 years and

was now giving us some answers about what was happening,” says Allison.

This agent, he claimed,

was so effective that he had even spent considerable time in

conversation with the Chinese leadership. “Petraeus was fascinated. Who

in the world could it be?”

Lee

Kuan Yew (right) with then Chinese premier Li Peng in Beijing, on

September 15, 1988, during the then Singapore prime minister’s official

visit to China. Picture: AFP

Lee

Kuan Yew (right) with then Chinese premier Li Peng in Beijing, on

September 15, 1988, during the then Singapore prime minister’s official

visit to China. Picture: AFP

The answer, as Allison

gleefully revealed, was Lee, whose success in transforming Singapore

economically while maintaining authoritarian political control

fascinated China’s elites.

“He penetrated the Chinese

mind and trajectories,” says Allison. “He had become a leader of such

status that all the Chinese leaders called him ‘Mentor’. He didn’t have

any fear about what he was prepared to say. He was always very blunt and

straight-spoken.”

Allison offers an example straight out of the Thucydides Trap.

“When the question is:

are China’s leaders really serious about displacing the US as the

predominant power in Asia in the foreseeable future? Most Chinese

experts say, ‘Oh, it’s complicated.’ Lee Kuan Yew’s answer was, ‘Of

course! Why not?’”

The

notion that China is going to accept its place in the American-defined

international order [in] the way Japan and Germany, as Lee said, did is a

fiction. China wants to be accepted as China, not as an honorary

member of the West

Lee convinced Allison that China is not interested in power on anyone’s terms other than its own.

“The notion that China is

going to accept its place in the American-defined international order

[in] the way Japan and Germany, as Lee said, did is a fiction. China

wants to be accepted as China, not as an honorary member of the West,”

he says.

In this context, China

challenges the traditional Thucydides Trap in one important regard: can

it be seen as the rising power? Indeed, Destined for War cites

statistics that suggest the country has already surpassed the US in

several key areas, including production of ships, steel, aluminium,

cellphones and computers, and the purchasing of cars.

President Xi Jinping. Picture: AFP

President Xi Jinping. Picture: AFP

“China

is not just a normal rising power,” says Allison. “China conceives

itself as being the dominant power in the world forever: ‘There was this

small diversion – the centuries of humiliation – but that was then. We

have re-emerged and if you [the US] will simply butt out, we will go

back to history as usual, as we conceive it.’”

Nevertheless, as Xi

pointed out in Seattle, the perception of facts is often as important as

the facts themselves. Allison argues that while the economic gap

separating China from the US may be closing fast, the latter is still

broadly regarded as the dominant superpower, even in Asia.

“The US – and I subscribe

to most of this – has been a benevolent hegemon and created an

international order, and nowhere more clearly than in Asia,” says

Allison. “It has been of enormous benefit to everybody. You have never

seen such economic prosperity as occurred in the economic and security

order that the US created after World War Two and which has been

maintained in the decades since. In the American view – that this has

been fantastic for everybody, and China should be thankful and actually

should be prepared to be supportive of this order, of which it has been

the beneficiary – this makes complete sense.”

What Trump could learn from the Great Wall of China’s troubled history

He adds: “Thucydides would say this is always how ruling powers see things.”

If the potential for

rivalry is hard to refute, what about the potential for actual conflict?

Allison’s introductory observations give reasons to be cheerful.

“I don’t think there’s a

single person in Washington that thinks war with China is a good idea,”

the writer says. “I have never met such a person. And I don’t believe

there is a single person in the Chinese military or defence

establishment who believes this would be a good idea.”

US President Donald Trump. Picture: AFP

US President Donald Trump. Picture: AFP

One

primary danger inherent in a Thucydides Trap is how it undermines a

shared determination against war, and that conflict can begin in the

most unlikely of places. Allison points to the first world war, whose

flashpoint was the Balkans.

“Right now, the most

dangerous hot spot in the world is Korea,” says Allison, “and it is a

very plausible path to Americans and Chinese in a war that would be

insane and that neither would want, and afterwards both would repent.”

Korea, unlike the Balkans in 1913, stages a direct competition between the two Thucydidean powers.

“As a Chinese high-level

official told me two weeks ago in Beijing,” says Allison, “‘there would

not be a problem on the Korean peninsula if [the US] weren’t there. This

is a country on our border. What are you doing there?’”

Allison’s response aligns with American foreign policy.

“South Korea for the

Americans and for me is a great success story,” he says. “We regard this

as a poster child for successful American Asian order. But I can

understand how from the Chinese perspective it does look like an

American military ally very close to their border.”

Destined For War by Graham Allison

Destined For War by Graham Allison

Rhetoric

and tensions have been heated up by the election of US President Donald

Trump, who keeps an uncharacteristically low profile in Allison’s

book. This is largely due to timing – Destined for War was all

but complete when Trump was elected last November. “This is not a Trump

book,” says Allison. But has Trump changed the trajectory of Allison’s

newest Thucydides Trap?

“I am not 100 per cent

clear,” the writer says. “Here is somebody who in the campaign basically

demonised China. He came to office not knowing much about the history

or realities or issues of international politics, and almost fell into a

deep hole with Taiwan. Then, when he discovered how deep he was in, he

reversed course immediately, so he shows great capacity for learning.”

Whether similar capacity

is visible in Trump’s dealings with North Korea is less obvious. He

seems not to have been aware of the DPRK, much less the threat posed by

Kim Jong-un, until Barack Obama told him about it in their handover

meeting.

“Trump was shocked,” says Allison. “Two hours later, he said, ‘Not going to happen!’ He has been saying that ever since.”

Trump as JFK? How haters and the media are underestimating the US president on North Korea

Trump’s military advisers

(the hawkish James Mattis and H.R. McMaster) have consistently argued

that they have the capability to prevent Kim attacking South Korea.

Allison imagines a scenario.

“We suspect North Korea

are going to rain down artillery shells on Seoul, which can kill half a

million, a million people, in 24 hours,” he says. “That means a second

Korean war. As Mattis testified [in May], this is going to be the

bloodiest war anybody will have seen in their lifetime. We would have

seen nothing like this since the last Korean war. [Mattis says] we can

win that war and eliminate Kim Jong-un, except if China enters the war.”

Could this be the endgame in a Thucydides Trap? Would China intervene?

US Secretary of Defence James Mattis (right) with National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster. Picture: AFP

US Secretary of Defence James Mattis (right) with National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster. Picture: AFP

“That’s a good question.

Why is China not going to enter the war? The answer is, ‘That would be

crazy.’ That would mean war with the US. Was that crazy in 1950? How did

that work out? Not very well.”

If China, fearing a

unified Korea, did support the North, while the US supported the South,

could such a conflict remain local, or would it escalate – as cyberwar

or something considerably more damaging? Should he get an opportunity,

Allison has advice for both Xi and Trump. That advice is refreshingly

odd. “[The English philosopher] Hobbes taught us there are no superior

authorities,” says Allison. “Nobody is superior to Trump and Xi, but

imagine there were. Imagine a Martian strategist who parachutes down to

Xi and Trump, and says, ‘Guys, I have a few things to point out to

you.’”

Having begun by reminding

the pair of the historical dangers of the Thucydides Trap, the Martian

would argue that the greatest dangers to both leaders exist within their

own borders. “‘The fundamental problem that each of you face, and that

each of your societies faces, is whether you are going to be able to

govern yourself. I am betting against each of you.’”

The big chasm between China and US over the North Korean threat

For Xi, Allison’s Martian

argues, this means “trying to run a retro authoritarian system in an era

when people have smartphones. As Lee Kuan Yew told you, ‘That is an

operating system that is not going to work.’”

Trump, for his part, is

“trying to lead a dysfunctional democracy, which in part is how you got

elected, but which seems so paralysed and so poisonous in its politics

that it is genuinely a question whether you are going to be able to

govern yourself successfully. And that’s just for starters. I have 15

more problems for you.”

To avoid the Thucydides

Trap, Allison suggests that Xi and Trump take a leaf out of Thucydides’

account, and consider how Athenian politician Pericles proposed a

30-year peace treaty.

“Pericles figured out that

Athens and Sparta had enough problems to work on themselves,” says

Allison, “and they should take a breather for 30 years and mostly work

on their own problems.”

Graham Allison

Graham Allison

While Allison says he wants Destined for War

to inspire debate, several scholars have taken issue with everything

from his knowledge of China to his interpretation of Thucydides.

According to Arthur Waldron, Lauder professor of international relations

at the University of Pennsylvania, Allison’s praise of Pericles does

not tell the whole story. “In fact,” Waldron argues, “war began when

Athens intentionally violated the 30-year truce in order to teach Sparta

a lesson.”

Waldron also criticises

what he calls Harvard’s “China fever”, adding, “Allison, like Kissinger,

has constructed a China according to his own specifications. Recently

in China, a high-level think-tanker said to me, ‘Arthur, what do we do

now? Everyone knows the system doesn’t work. But how do you change it

without making things worse, setting off a civil war? We are at a dead

end.’

“If Allison could have sat

down with this fellow, it would have done him a world of good, but he

can’t talk to him, or read Chinese, or even meet the guy.”

Where Waldron and

Allison might find common ground is in endorsing the study of history

as an antidote to potential doom, and Allison cites Spanish philosopher

and writer George Santayana’s famous warning, “Those who forget the past

are condemned to repeat it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment