AstronomyStrange signals from the sky may be signs of aliens

Or maybe something equally weird, but not alive

ON

AUGUST 24th 2001 the Parkes Observatory, in Australia, picked up an

unusual signal. It was a burst of radio waves coming more or less from

the direction of the Small Magellanic Cloud, a miniature galaxy that

orbits the Milky Way. This burst was as brief as it was potent. It

lasted less than 5 milliseconds but, during that period, shone with the

power of 100m suns. It was, though, noticed by astronomers only in 2007,

when they were poking around in Parkes’s archived data. As far as they

can tell, it has never been repeated.

Similar unrepeated signals have since been noted elsewhere in the heavens. So far, 17 such “fast radio bursts” (FRBs) have been recognised. They do not look like anything observed before, and there is much speculation about what causes them. One possibility is magnetars—highly magnetised, fast-rotating superdense stars. Another is a particularly exotic sort of black hole, formed when the centrifugal force of a rotating, superdense star proves no longer adequate to the task of stopping that star collapsing suddenly under its own gravity. But, as Manasvi Lingam of Harvard University and Abraham Loeb of the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics observe, there is at least one further possibility: alien spaceships.

Specifically, the two researchers suggest, in a paper to be published in Astrophysical Journal Letters,

that FRBs might be generated by giant radio transmitters designed to

push such spaceships around. With the rotation of the galaxies in which

these transmitters are located, the transmitter-beams sweep across the

heavens. Occasionally, one washes over Earth, producing an FRB.

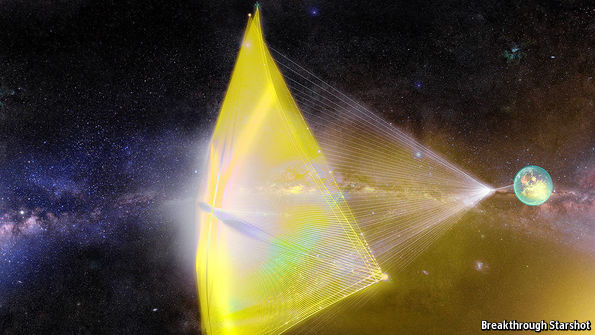

This idea is not completely mad. Human rocket scientists have toyed with something similar, in order to overcome one of the biggest problems of spaceship design: that a craft propelled by a rocket motor must carry its fuel with it. Fuel has mass. That mass must be moved by more fuel—which adds more mass to the craft, which thus needs still more fuel. And so on. For this reason, 90% or more of a conventional rocket’s launch mass is its fuel.

It is possible, though, to separate the fuel from the craft. That is the principle behind a solar sail, which employs the gentle pressure exerted by sunlight to propel a vehicle. A nippier alternative is to use focused light beams to provide the pressure. Yuri Milner, a Russian billionaire with a long-standing interest in science, is paying for research into such a machine. He proposes to drive a tiny probe to Alpha Centauri, one of Earth’s nearest stellar neighbours, using banks of powerful lasers.

Dr Lingam and Dr Loeb suggest FRBs might be the result of vastly bigger takes on the same principle, except that they employ the radio portions of the electromagnetic spectrum rather than visible light. The two researchers have worked out what would be needed if the transmitter behind such a burst were solar-powered. They calculate that the amount of sunlight falling onto a planet about twice the size of Earth, and at the right distance from its star to have liquid water on its surface, would yield enough energy to accelerate a spaceship weighing a million tonnes or so to a speed close to that of light before the propulsion beam became too attenuated to propel it any faster. This would be perfect for ferrying large numbers of beings from one star system to another, as long as there was an equivalent device at the other end to slow the craft down again.

To check whether such a machine is technologically plausible, the two researchers calculated that the necessary planet-sized array of radio transmitters could be kept cool by nothing more exotic than ordinary water. So, as far as they can see, while building such a machine would be a heroic feat of engineering, nothing in the laws of physics actually forbids it.

Saying that the features of FRBs are consistent with their being signs of an alien space-propulsion system is not, of course, the same as saying that this is what they actually are. One early explanation of pulsars—regular cosmic radio signals first observed in 1967 was that they were alien radio beacons. They later turned out to be caused by fast-spinning neutron stars. For physicists, though, that explanation was almost as interesting. A neutron star is one whose protons and electrons have merged with each other to create neutrons. These, together with the star’s pre-existing neutrons, result in an object that has no atoms in it. Since atoms are composed mostly of empty space a neutron star, instead of being star size, is just a few kilometres across. If FRBs turn out to be even a fraction as curious as that, most astronomers would forgive them for not being artificial.

Similar unrepeated signals have since been noted elsewhere in the heavens. So far, 17 such “fast radio bursts” (FRBs) have been recognised. They do not look like anything observed before, and there is much speculation about what causes them. One possibility is magnetars—highly magnetised, fast-rotating superdense stars. Another is a particularly exotic sort of black hole, formed when the centrifugal force of a rotating, superdense star proves no longer adequate to the task of stopping that star collapsing suddenly under its own gravity. But, as Manasvi Lingam of Harvard University and Abraham Loeb of the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics observe, there is at least one further possibility: alien spaceships.

Latest updates

Angela Merkel and her press corps show how big democracies are supposed to operate

Free health cover for Britons in Europe is under threat

Where others gawked, John Samson looked with genuine curiosity

Donald Trump’s “America First” budget would make deep cuts to domestic programmes

Hundreds of thousands of people have fled South Sudan for Uganda

An array of churches opposes Donald Trump’s proposed cuts to foreign aid

This idea is not completely mad. Human rocket scientists have toyed with something similar, in order to overcome one of the biggest problems of spaceship design: that a craft propelled by a rocket motor must carry its fuel with it. Fuel has mass. That mass must be moved by more fuel—which adds more mass to the craft, which thus needs still more fuel. And so on. For this reason, 90% or more of a conventional rocket’s launch mass is its fuel.

It is possible, though, to separate the fuel from the craft. That is the principle behind a solar sail, which employs the gentle pressure exerted by sunlight to propel a vehicle. A nippier alternative is to use focused light beams to provide the pressure. Yuri Milner, a Russian billionaire with a long-standing interest in science, is paying for research into such a machine. He proposes to drive a tiny probe to Alpha Centauri, one of Earth’s nearest stellar neighbours, using banks of powerful lasers.

Dr Lingam and Dr Loeb suggest FRBs might be the result of vastly bigger takes on the same principle, except that they employ the radio portions of the electromagnetic spectrum rather than visible light. The two researchers have worked out what would be needed if the transmitter behind such a burst were solar-powered. They calculate that the amount of sunlight falling onto a planet about twice the size of Earth, and at the right distance from its star to have liquid water on its surface, would yield enough energy to accelerate a spaceship weighing a million tonnes or so to a speed close to that of light before the propulsion beam became too attenuated to propel it any faster. This would be perfect for ferrying large numbers of beings from one star system to another, as long as there was an equivalent device at the other end to slow the craft down again.

To check whether such a machine is technologically plausible, the two researchers calculated that the necessary planet-sized array of radio transmitters could be kept cool by nothing more exotic than ordinary water. So, as far as they can see, while building such a machine would be a heroic feat of engineering, nothing in the laws of physics actually forbids it.

Saying that the features of FRBs are consistent with their being signs of an alien space-propulsion system is not, of course, the same as saying that this is what they actually are. One early explanation of pulsars—regular cosmic radio signals first observed in 1967 was that they were alien radio beacons. They later turned out to be caused by fast-spinning neutron stars. For physicists, though, that explanation was almost as interesting. A neutron star is one whose protons and electrons have merged with each other to create neutrons. These, together with the star’s pre-existing neutrons, result in an object that has no atoms in it. Since atoms are composed mostly of empty space a neutron star, instead of being star size, is just a few kilometres across. If FRBs turn out to be even a fraction as curious as that, most astronomers would forgive them for not being artificial.

No comments:

Post a Comment