The South China Sea’s Worsening Strategic Dilemmas

The

world has moved on but most South China Sea strategies are stuck in the

past. For example, Australia’s policies have changed very little from 2011 to today. So instead, let’s think about strategies for the future. China first became more assertive seven years ago; what could the South China Sea be like seven years from now?

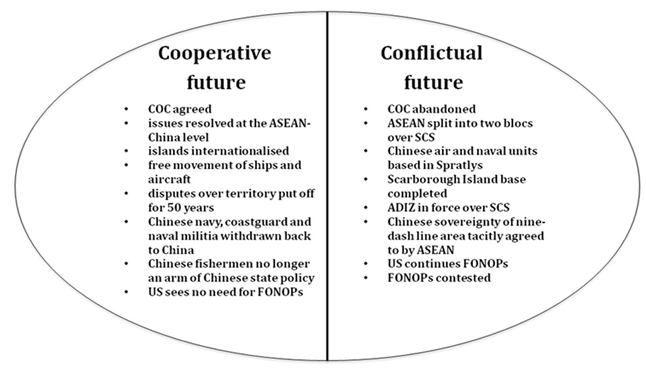

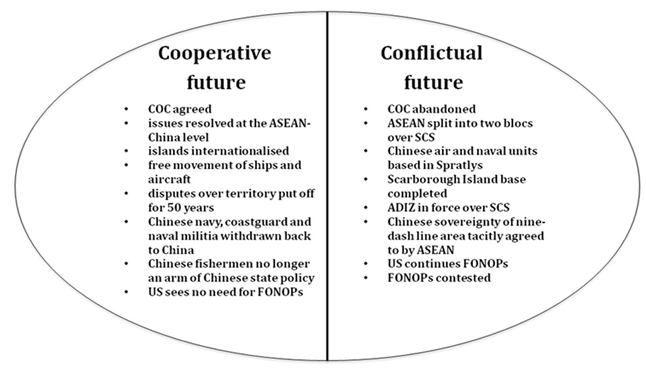

Alternative futures represent a way for us to think about possible tomorrows. Imagine that the future lies somewhere between the best of all possible worlds and the worst, somewhere between a cooperative and a conflictual state. Neither extreme future is necessarily more likely than the other, but they allow us to think about the spectrum of possibilities. Using the cooperative and conflictual variables creates two possible alternative 2023s:

The cooperative future will be considered by many to be wildly

optimistic, while pessimistic realists will say that the conflictual

world bears some resemblance to where we are now. But the task for

policymakers is to steer the future towards the ‘good’ tomorrow and away

from the ‘bad’ one. Worryingly, the two major strategic thrusts at the

moment, driven by ASEAN and the United States, don’t seem to be moving

us in the good direction. .

The cooperative future will be considered by many to be wildly

optimistic, while pessimistic realists will say that the conflictual

world bears some resemblance to where we are now. But the task for

policymakers is to steer the future towards the ‘good’ tomorrow and away

from the ‘bad’ one. Worryingly, the two major strategic thrusts at the

moment, driven by ASEAN and the United States, don’t seem to be moving

us in the good direction. .

ASEAN is trying to encourage China to sign a Code of Conduct (COC), an agreement conceived as a binding preventive diplomacy measure that’ll forestall conflict. Talks continue, as they have since 2002. Late 2017 is now the hoped-for target date for completion of the code, or at least an agreed draft. China though has long argued—and formalised in various international agreements—that the South China Sea isn’t a multilateral issue and so ASEAN as a grouping has no place discussing it. And in recent years China has convinced Cambodia, Laos and now the Philippines to embrace the PRC’s South China Sea stance, making an ASEAN South China Sea consensus unlikely. More pointedly, why would China sign something that doesn’t advance its interests?

America’s strategy in the South China Sea is much more narrowly focussed. In periodic Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS), US Navy ships sail close to China’s new reclaimed islands. However, it’s hard to see that achieves anything long-lasting. At some time China may play hardball and try to deny access, probably using fishing vessels and its new large Coast Guard ships. The US wants its allies to join in those FONOPS, causing some political ructions in Australia about timing and whether sailing too close might escalate tensions. But the real issue is that such operations are ultimately meaningless in terms of helping create a better future world.

The main problem is that China holds the strategic initiative. At great cost, China has built six large islands in the South China Sea: three are substantial airbases and three host sizeable electronic surveillance installations. The scale of those new facilities is such that China can deploy an air combat force larger and more capable than any current ASEAN air force (with the possible exception of Singapore) off northern Borneo when it wishes. Given that, China can now easily enforce an Air Defence Identification Zone across the South China Sea when the time is deemed right. Most worryingly, for the first time China poses a realistic air threat to Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and all of Borneo. China today militarily dominates the central ASEAN region thanks to those new airbases, and has effectively relocated itself to the geographic heart of ASEAN.

China has changed the ‘facts on the ground’. It won’t suddenly abandon its costly new facilities even if ASEAN develops an acceptable COC or America continues its FONOPS. China’s new military bases are now a permanent part of the core ASEAN region. The incoming Trump administration can’t change that new reality, and so far shows little desire to try.

This may seem a vision of despair, and to some extent, it is. There may be ways to move towards the envisaged ‘better’ South China Sea future, but there’s little appetite to impose the necessary costs on China to force a change of tack. Such costs cut both ways and no one—ASEAN, America or America’s allies—wishes to bear the imposts.

So the time might be right to embrace a risk management approach rather than a South China Sea strategy. It’s too late to try to solve the South China Sea disputes but not to limit the harm that China’s new island bases might inflict on their closer ASEAN neighbours, especially Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. Those middle power states are both particularly important to Australia and geographically near.

In risk management terms, the aim would be to enhance the resilience of those states to Chinese pressure, threats and coercive diplomacy. The inward domestic focus of some of these nations might seem to preclude such an approach, but building resilience is internally, not outwardly, directed. Resilience threatens no one, while potentially minimising the political, diplomatic and military usefulness the new islands might have for China in times of peace, crisis or limited conflict. It’s time for some future-leaning policymaking.

Peter Layton is a Visiting Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University.

Alternative futures represent a way for us to think about possible tomorrows. Imagine that the future lies somewhere between the best of all possible worlds and the worst, somewhere between a cooperative and a conflictual state. Neither extreme future is necessarily more likely than the other, but they allow us to think about the spectrum of possibilities. Using the cooperative and conflictual variables creates two possible alternative 2023s:

ASEAN is trying to encourage China to sign a Code of Conduct (COC), an agreement conceived as a binding preventive diplomacy measure that’ll forestall conflict. Talks continue, as they have since 2002. Late 2017 is now the hoped-for target date for completion of the code, or at least an agreed draft. China though has long argued—and formalised in various international agreements—that the South China Sea isn’t a multilateral issue and so ASEAN as a grouping has no place discussing it. And in recent years China has convinced Cambodia, Laos and now the Philippines to embrace the PRC’s South China Sea stance, making an ASEAN South China Sea consensus unlikely. More pointedly, why would China sign something that doesn’t advance its interests?

America’s strategy in the South China Sea is much more narrowly focussed. In periodic Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS), US Navy ships sail close to China’s new reclaimed islands. However, it’s hard to see that achieves anything long-lasting. At some time China may play hardball and try to deny access, probably using fishing vessels and its new large Coast Guard ships. The US wants its allies to join in those FONOPS, causing some political ructions in Australia about timing and whether sailing too close might escalate tensions. But the real issue is that such operations are ultimately meaningless in terms of helping create a better future world.

The main problem is that China holds the strategic initiative. At great cost, China has built six large islands in the South China Sea: three are substantial airbases and three host sizeable electronic surveillance installations. The scale of those new facilities is such that China can deploy an air combat force larger and more capable than any current ASEAN air force (with the possible exception of Singapore) off northern Borneo when it wishes. Given that, China can now easily enforce an Air Defence Identification Zone across the South China Sea when the time is deemed right. Most worryingly, for the first time China poses a realistic air threat to Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and all of Borneo. China today militarily dominates the central ASEAN region thanks to those new airbases, and has effectively relocated itself to the geographic heart of ASEAN.

China has changed the ‘facts on the ground’. It won’t suddenly abandon its costly new facilities even if ASEAN develops an acceptable COC or America continues its FONOPS. China’s new military bases are now a permanent part of the core ASEAN region. The incoming Trump administration can’t change that new reality, and so far shows little desire to try.

This may seem a vision of despair, and to some extent, it is. There may be ways to move towards the envisaged ‘better’ South China Sea future, but there’s little appetite to impose the necessary costs on China to force a change of tack. Such costs cut both ways and no one—ASEAN, America or America’s allies—wishes to bear the imposts.

So the time might be right to embrace a risk management approach rather than a South China Sea strategy. It’s too late to try to solve the South China Sea disputes but not to limit the harm that China’s new island bases might inflict on their closer ASEAN neighbours, especially Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. Those middle power states are both particularly important to Australia and geographically near.

In risk management terms, the aim would be to enhance the resilience of those states to Chinese pressure, threats and coercive diplomacy. The inward domestic focus of some of these nations might seem to preclude such an approach, but building resilience is internally, not outwardly, directed. Resilience threatens no one, while potentially minimising the political, diplomatic and military usefulness the new islands might have for China in times of peace, crisis or limited conflict. It’s time for some future-leaning policymaking.

Peter Layton is a Visiting Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University.

No comments:

Post a Comment