Analysts: China Will be Able to Police Rival Countries in Disputed Sea

FILE - Construction is shown on Fiery Cross Reef, in

the Spratly Islands, the disputed South China Sea in this March 9, 2017,

satellite image released by CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

TAIPEI —

China’s near completion of artificial islets and combat aircraft

facilities in the Spratly Islands will give it extra power to make other

countries keep out of the widely disputed South China Sea or get

Chinese permission to use it, analysts say.

Beijing is about to finish naval, air, radar and other facilities on the “big three” islets in the sea’s Spratly archipelago, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, a project of the Washington-based policy research organization Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The American think tank initiative’s monitoring over the past two years shows a near completion of “major construction of military and dual-use infrastructure” on Subi, Mischief and Fiery Cross reefs held by China in the Spratlys, according to its website, which adds Beijing can now deploy combat aircraft and mobile missile launchers to the Spratly Islands anytime.

Around-the-clock presence in area

Those installations will give China “around-the-clock presence” for “establishing administration” over its claims to the 3.5 million-square-kilometer sea, initiative director Gregory Poling said.

China claims more than 90 percent of the resource-rich sea that extends from Taiwan southwest to Singapore. The Chinese claim overlaps tracts that Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam also call their own.

“If you’re a Southeast Asian fisherman or coast guard vessel or an oil and gas exploration vessel, you don’t operate unless the Chinese let you operate, because they now are watching everything you do, and as soon as they send planes out there they’ll be able to intervene anywhere, anytime,” Poling said.

Fishing boats from other countries eventually must register with the Chinese to use the disputed sea, said Alex Chiang, an international relations professor at National Chengchi University in Taipei. Vessels now trawl freely in 370-kilometer exclusive economic zones extending from their home countries’ coastlines.

China’s enforcement ability may be tested when the country implements a fishing moratorium from May through August, Poling said. The moratorium would let stocks regenerate in the northern half of the sea.

Officials in Beijing are talking one on one with the Southeast Asian maritime claimants to offer them trade and investment benefits from China’s $11 trillion economy, some believe in exchange for letting China do what it wants at sea.

Those talks picked up after July when a world arbitration court ruled at the request of the Philippines against the legal basis for China’s maritime claim. China cites historic usage records to back its claim and has rejected the court ruling.

Vietnam lacks confidence in US

In Vietnam, officials are starting to deal with China’s consolidation of maritime power for lack of confidence in U.S. support, said Oscar Mussons, senior associate with the Dezan Shira & Associates business consultancy in Ho Chi Minh City.

U.S. President Donald Trump has not made it clear whether he will back the Southeast Asian countries over China, analysts in the region believe.

“At some point Vietnam felt strong and said well, we have the United States backing us, so it’s going to be fine,’ but nobody knows what’s going on with the United States,” Mussons said.

Vietnamese officials are keeping quiet and talking to Beijing about economic cooperation as China develops the sea, he said, but citizens are protesting passively by avoiding made-in-China products.

“They don’t really say we need to fight them back,’“ he said. “But of course they’ve always seen China as a threat, and I think that’s the way it’s going to be for a while now if things don’t change.”

Since 2010 China has quickly expanded into the sea, landfilling more than 12 square kilometers to make reefs ready for construction of facilities.

China’s three air bases in the Spratlys and another on Woody Island in the Paracel Island archipelago, which is contested by Vietnam, will allow Chinese military aircraft to operate over nearly the entire South China Sea, the initiative says.

The government in Beijing will know what other countries are doing via advanced surveillance and early-warning radar facilities at Fiery Cross, Subi and Cuarteron Reefs in the Spratly chain, as well as Woody Island, the initiative’s website adds.

Beijing is about to finish naval, air, radar and other facilities on the “big three” islets in the sea’s Spratly archipelago, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, a project of the Washington-based policy research organization Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The American think tank initiative’s monitoring over the past two years shows a near completion of “major construction of military and dual-use infrastructure” on Subi, Mischief and Fiery Cross reefs held by China in the Spratlys, according to its website, which adds Beijing can now deploy combat aircraft and mobile missile launchers to the Spratly Islands anytime.

Around-the-clock presence in area

Those installations will give China “around-the-clock presence” for “establishing administration” over its claims to the 3.5 million-square-kilometer sea, initiative director Gregory Poling said.

China claims more than 90 percent of the resource-rich sea that extends from Taiwan southwest to Singapore. The Chinese claim overlaps tracts that Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam also call their own.

“If you’re a Southeast Asian fisherman or coast guard vessel or an oil and gas exploration vessel, you don’t operate unless the Chinese let you operate, because they now are watching everything you do, and as soon as they send planes out there they’ll be able to intervene anywhere, anytime,” Poling said.

Fishing boats from other countries eventually must register with the Chinese to use the disputed sea, said Alex Chiang, an international relations professor at National Chengchi University in Taipei. Vessels now trawl freely in 370-kilometer exclusive economic zones extending from their home countries’ coastlines.

FILE - Protesters display placards in front of the

Chinese Consulate to protest China's alleged continuing "militarization"

of the disputed islands off the South China Sea including a plan to

build a monitoring station on Scarborough Shoal, March 24, 2017.

“I think (China) will draw the line where those fishing boats can

operate and they will require those fishing boats to get permission

from China first in order to operate in the area, so that means all

other countries have to observe Chinese domestic law,” Chiang said.China’s enforcement ability may be tested when the country implements a fishing moratorium from May through August, Poling said. The moratorium would let stocks regenerate in the northern half of the sea.

Officials in Beijing are talking one on one with the Southeast Asian maritime claimants to offer them trade and investment benefits from China’s $11 trillion economy, some believe in exchange for letting China do what it wants at sea.

Those talks picked up after July when a world arbitration court ruled at the request of the Philippines against the legal basis for China’s maritime claim. China cites historic usage records to back its claim and has rejected the court ruling.

Vietnam lacks confidence in US

In Vietnam, officials are starting to deal with China’s consolidation of maritime power for lack of confidence in U.S. support, said Oscar Mussons, senior associate with the Dezan Shira & Associates business consultancy in Ho Chi Minh City.

U.S. President Donald Trump has not made it clear whether he will back the Southeast Asian countries over China, analysts in the region believe.

“At some point Vietnam felt strong and said well, we have the United States backing us, so it’s going to be fine,’ but nobody knows what’s going on with the United States,” Mussons said.

Vietnamese officials are keeping quiet and talking to Beijing about economic cooperation as China develops the sea, he said, but citizens are protesting passively by avoiding made-in-China products.

“They don’t really say we need to fight them back,’“ he said. “But of course they’ve always seen China as a threat, and I think that’s the way it’s going to be for a while now if things don’t change.”

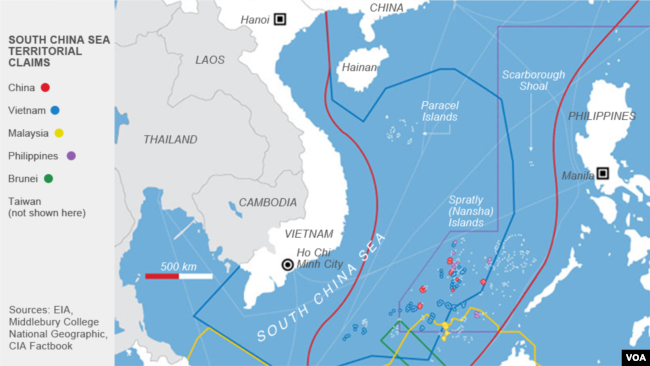

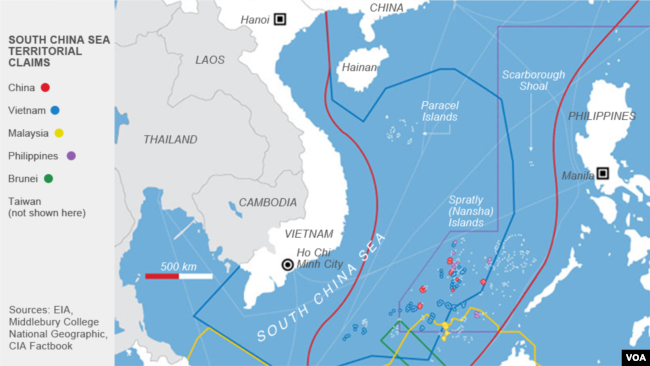

South China Sea Territorial Claims

Claimant countries prize the tropical sea for fisheries and

undersea reserves of oil and gas. Also, more than half the world’s

marine shipping traffic uses the waterway. Like China, Taiwan claims

nearly the whole sea. Other governments operate in zones near their

coastlines, and all the claimants control tiny land forms in the Spratly

chain.Since 2010 China has quickly expanded into the sea, landfilling more than 12 square kilometers to make reefs ready for construction of facilities.

China’s three air bases in the Spratlys and another on Woody Island in the Paracel Island archipelago, which is contested by Vietnam, will allow Chinese military aircraft to operate over nearly the entire South China Sea, the initiative says.

The government in Beijing will know what other countries are doing via advanced surveillance and early-warning radar facilities at Fiery Cross, Subi and Cuarteron Reefs in the Spratly chain, as well as Woody Island, the initiative’s website adds.

No comments:

Post a Comment